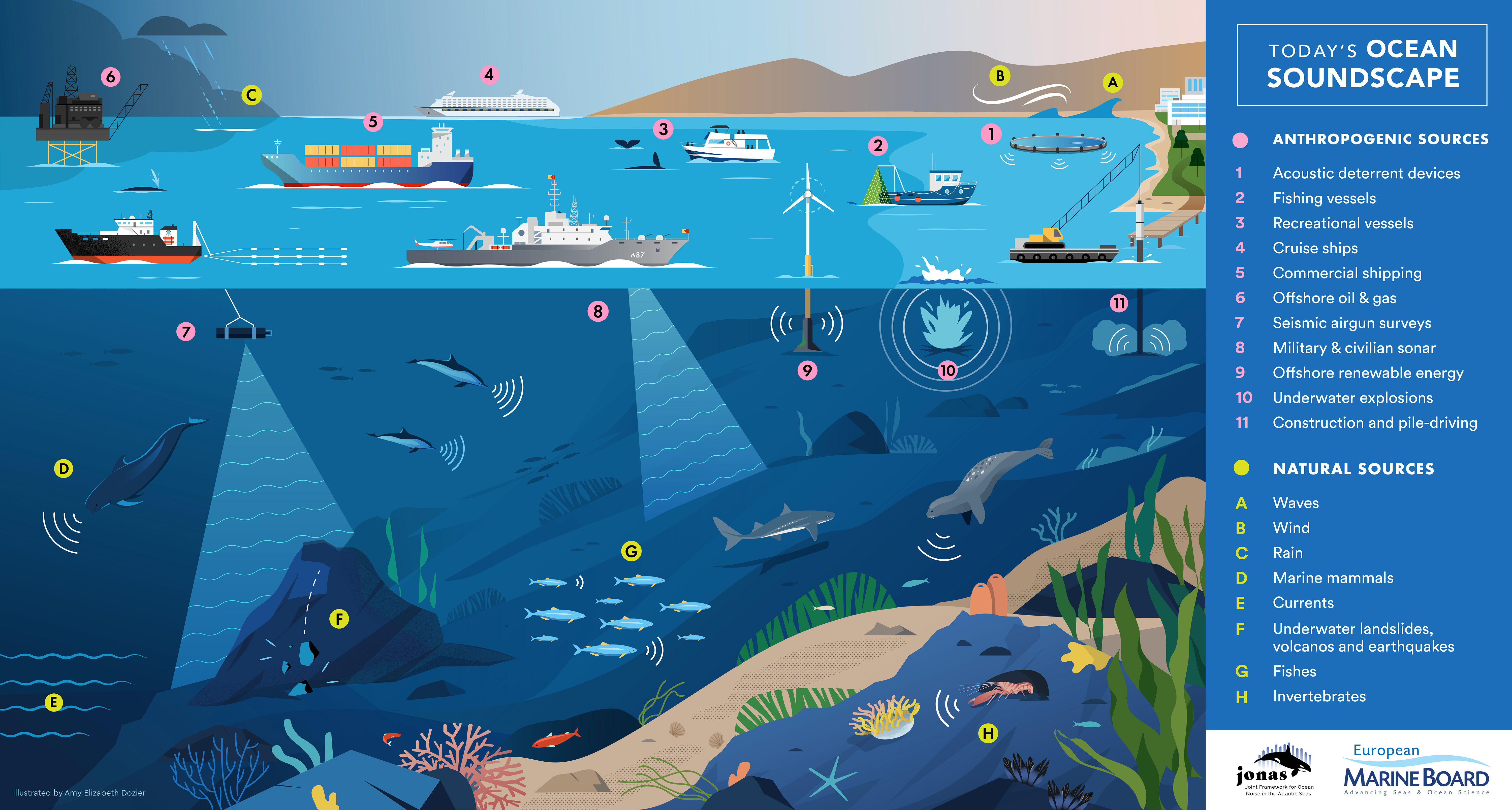

Underwater noise has become well-recognized as a pollutant of concern in the marine environment. Given the limited penetration of light in the ocean, sound is the predominant way marine species gain information about the world surrounding them. With human activity in the ocean increasing, resulting underwater noise is also steadily increasing with detrimental impacts on marine organisms. Academia, governments, industries and non-governmental organizations recognize that underwater noise and its impacts should be monitored, mitigated and managed. Underwater noise is now explicitly addressed within a number of policy and regulatory frameworks. Thanks to ongoing science communication activities, societal awareness of the topic is also increasing.

Underwater noise is different to other forms of pollution in that it is transient, and will stop once the sound generating operation stops, although the effects of underwater noise on species may last longer than the sound itself. The marine science, engineering and acoustics communities already have a good, if incomplete, understanding of anthropogenic underwater sound, the effects of noise on marine species, and how to manage underwater noise. Some important sources of underwater noise include air-guns, shipping, pile-driving and dredging. Regional initiatives have been established to create noise registers, to measure and map baseline ambient noise, and to conduct joint noise monitoring programs, with long-term trends in underwater noise now beginning to be studied.

There is also a solid foundation of knowledge on the ability of marine animals to hear and use sound, especially for marine mammals, which is essential for understanding how noise may affect these species. It is now recognized that underwater noise (in the form of sound pressure and/or particle motion, which is the oscillatory movement of water particles due to the influence of the vibrating sound source) is detected by, and therefore potentially harmful to, fish, invertebrates and even plant species. To further knowledge development, the marine science community has started to collaborate with other disciplines (e.g., naval engineering, acoustics, autonomous sensing) to study, for example, behavioral responses to noise, or to understand the mechanisms behind a series of beaked whale strandings following exposure to some types of military sonar. Emerging innovative technologies will also support this research, for example the use of drones to track and observe the behavior of marine mammals.

Ship passing Terneuzen, the Netherlands. (Image credit: European Marine Board)

When it comes to managing underwater noise, the international, explicit acknowledgement of noise as a pressure on marine ecosystems has driven further action to address it. In Europe, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) has been the key initiator of action taken by Member States and Associated Countries to understand underwater noise baselines and impacts, leading to the development of appropriate mitigation strategies. There has also been international and often sectoral action on mitigating underwater noise sources, such as work at the International Maritime Organization (IMO) on addressing shipping noise. A number of regulatory measures tailored to other specific sources have been developed by international and/or regional sectoral bodies, such as for pile-driving and military sonar. However, as discussed shortly, there is more that we must understand and do to take the next step forward in addressing this pollutant.

While all new knowledge on underwater noise is useful, some areas of research are more helpful than others to directly improve management strategies. It is important to prioritize both research into key evidence gaps, and the removal of barriers to progress in noise mitigation. This is what the Working Group on underwater noise, convened by the European Marine Board (EMB), aimed to do in their 2021 report: ‘Addressing underwater noise in Europe: Current state of knowledge and future priorities’. The following priority actions were identified for Europe (although many are applicable elsewhere) as those most likely to ultimately result in the proportionate and effective management and mitigation of underwater noise.

The availability of international standards for measuring and reporting underwater noise and its effects has been a gap that has hindered knowledge development, communication between stakeholder groups, and the comparison and combination of studies. Internationally agreed standards need to be developed to address all aspects of underwater noise. These should build on existing standards such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards for determination of sound levels at their source from deep-water measurements (2016) and for terminology used in underwater acoustics (2017). These standards must be internationally agreed and implemented, which requires transdisciplinary and global collaboration for their development.

In addition, comprehensive long-term monitoring of marine species’ habitat use, movements, behavior and distribution is fundamental to the assessment of noise exposure, dose-response and the management of the risk posed by noise. Significant progress will only be made if studies are appropriately supported with adequate funding and policy direction.

Today’s Ocean soundscape including anthropogenic and natural sound sources, labelled anti-clockwise. (Image credit: Amy Dozier / European Marine Board / JONAS Project)

Comprehensive data on soundscapes is also key. The MSFD has led to a number of regional joint noise monitoring programs in Europe (e.g., in the Baltic, North and Mediterranean Seas, and the Atlantic Ocean), which should continue over the long-term and expanded to new areas, e.g. where noise generation is expected to grow and/or where current capacity to address noise impacts is low.

Although a lot has already been done to characterize certain anthropogenic sound sources, there are still gaps: biologically relevant sound sources (i.e., those thought to be more damaging and/or persistent) should now be prioritized. This will require close collaboration between academia and industry, perhaps building on existing initiatives such as the E&P Sound and Marine Life Joint Industry Programme.

Interdisciplinary research collaborations are needed to inform further investigations into the effects of noise on marine animals. These should include studies to understand hearing abilities and behavioral responses to noise in marine species not yet studied in detail (e.g., non-commercial fish species and invertebrates); studies on hearing impairment and physiological stress in species in response to noise; and monitoring and modelling changes in acoustic habitats to understand masking risks. To gain the holistic understanding of the effects of noise that is needed to truly manage it, we also need to go beyond studying individuals and groups, and move towards studying species populations, multi-species systems, predator-prey- and food-web interactions. Dedicated research frameworks, which take a strategic and holistic view, are needed to guide studies on these complex interactions. These frameworks can also help us address the question of how noise interacts with other marine pollutants and stressors, and what the impacts of cumulative stressors are on marine species.

All this additional research should feed into the further development of underwater noise management. With appropriate knowledge transfer into governance, regulatory and industrial sectors, this information will be critical to delivering successful management strategies. In the meantime, these sectors should conduct studies into the effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of existing noise mitigation devices and measures, and management options. As well as developing new ideas, we also need to understand whether the current approaches for underwear noise management are working.

Given the trans-boundary nature of underwater noise and its impacts, they cannot be addressed by any one country or sector in isolation. Regional cooperation to develop noise action plans and mitigation guidelines as well as guidance for Environmental Impact Assessments will be needed to support more coordinated action, addressing the trans-boundary nature of noise.

The development of stakeholder and societal capacity is key to understanding and addressing underwater noise, including technical guidance and workshops, sharing of data and best practices, and support for communications. This will further help to bring the issues of underwater noise to relevant audiences.

This article and its recommendations are based on those presented in the EMB Future Science Brief on “Addressing underwater noise in Europe: Current state of knowledge and future priorities”. The Future Science Brief was launched on 20 October 2021 and can be downloaded from the EMB website: https://www.marineboard.eu/publications/addressing-underwater-noise-europe-current-state-knowledge-and-future-priorities

This feature appeared in Environment, Coastal & Offshore (ECO) Magazine's 2022 Autumn edition, to read more access the magazine here.