Facing the truth about microplastic in marine and coastal habitats

By Ana Carolina Moreira de Oliveira1; Ana Carolina de Azevedo Mazzuco2&3; Bianca Reis Castaldi Tocci2

1 Our Blue Hands project, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil

2 Deep Blue Associação Ambiental, Av. Dr. Moraes Sales 1654, 13010002, Campinas, Brazil

3 Benthic Ecology Group, Department of Oceanography, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari 514, 29075-910, Vitória, Brazil

Not very long ago, the Ocean used to be a richer and healthier place, where life was abundant and environments resilient. Human development to modern society has pressured nature to its limits and the consequences will be carried through generations. Single-use products have become a day to day habit and plastic is embedded in every minute of our lives, including before birth. Now, as we envision new goals for the Decade, including a Clean Ocean, the truth about plastic must be faced as a real complex problem affecting marine environments and human health.

Evidence of plastics in the Ocean and at the coastal zones is frequent, widespread, and vast. According to a preliminary census of marine litter, about 8 million tons of plastic are released every year into rivers and seas, with the a large amount being produced by highly populated nations, such as Brazil and China.

Plastic waste is often seen deposited on the beaches along the Brazilian coast, from crowded areas to wild seascapes. These dramatic scenes prove that even if people are not physically present at a site, their footprints in terms of marine litter are still there and have a huge impact on environmental quality.

In the Sand

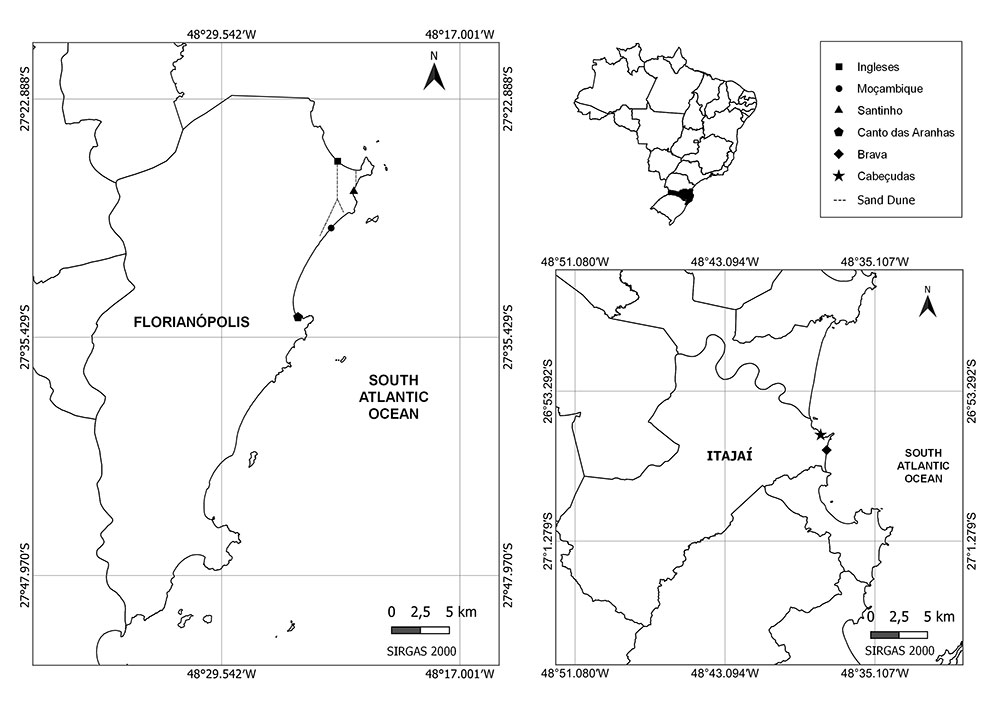

Unfortunately, assessing the presence of marine litter in the ocean does not require long-term efforts. After only a few months of sandy beach monitoring in Santa Catarina-Brazil by the Our Blue Hands Project (December 2020 to March 2021, six sites), marine litter was observed in every sampling campaign. When carefully searching in the sand, many types, sizes, and colors of plastic fragments could be found.

Preliminary results showed significant differences in microplastic composition between cities where these beaches were located (Itajaí and Florianópolis, less than 100 km apart) and potentially related to wave action. For example, primary microplastics were more frequent and abundant in Florianópolis, which is the larger city with beaches more exposed to waves and wind. Secondary microplastics, on the other hand, were common in Itajaí, a port city. These findings suggest that the sources of microplastics and accumulation processes vary markedly within a region, and variations should be considered by coastal managers.

Plastic release into marine environments occurs through a variety of pathways, such as river discharge, runoff, beach littering, tides, winds, and shipping activities. However, rivers and land-based releases are still so far considered the dominant source. Intemperization will reduce plastics into small particles, which will accumulate in certain areas of the coast and offshore. In order to map the main polluting sources and potential microplastics pathways to the beach, several factors are observed during monitoring, such as accessibility, urbanization, wave and wind exposure, rivers, and sewage discharge.

After five months of the Our Blue Hands monitoring, the fact that the environment directly influences the type of residue on the sand was clearly evident. Although the beaches in Florianópolis are beautiful and may even be considered pristine, there was a lot of microplastics accumulation in the sand, probably caused by the several urbanized areas and strong wind and wave transport.

Itajaí beaches had different types of plastic fragments, suggesting more diverse sources of pollution and an effect of the large freshwater supply from Itajaí-Açu hydrographic basin and port activities. The beaches with the highest number of people visiting and calm waters presented both micro and macro residues, with many single-use plastic fragments buried in the sand (e.g., straws, packaging, spoons).

Itajaí beaches had different types of plastic fragments, suggesting more diverse sources of pollution and an effect of the large freshwater supply from Itajaí-Açu hydrographic basin and port activities. The beaches with the highest number of people visiting and calm waters presented both micro and macro residues, with many single-use plastic fragments buried in the sand (e.g., straws, packaging, spoons).

One of the challenges of estimating the number of microplastics in Itajaí is that the beaches are cleaned daily. Sand scrapers end up mixing residue to deeper layers and it is necessary to dig 5 cm to find the micro-trash. Another unique feature in Itajaí is the outcrop of Cassino Lagoon, where freshwater meets the sea during spring tides and is a critical source of microplastics (pellets, pet bottles, toys, fishing nylon were sighted and collected during monitoring). Microplastics were even found in the Sambaquis, important archeological sites in the sand dunes on the Southeastern coast of Brazil.

The Plastic Footprint

The durability of plastic is both the solution for industries and a major concern for marine environments. In addition to entering marine ecosystems, plastics persist for many years along the shoreline, seabed, water column, and sea surface environments of the world’s ocean.

One of the most visible impacts of plastic pollution on marine environments is the effects of plastic fragments on marine life. For example, the populations of migratory birds, which rely mostly on marine resources, are drastically harmed by plastic fragments eaten during harvesting. Not only because of the amount of accumulated waste but also because of its toxicity. According to UNEP, 90 percent of seabirds have plastic in their stomachs, and these birds may consume smaller pieces such as virgin plastic pellets, synthetic fibers from clothes, and microbeads from cosmetics.

Images of dead birds, turtles and sea mammals with plastic in their stomach are very common, however, they are not just the ones negatively impacted by plastic pollution. Nowadays, plastic is literally found in every species and all habitats of the Ocean. Even tiny organisms such as marine phytoplankton are absorbing small plastic particles (e.g. nanoplastics) and, like all of us, are learning how to deal with this stress. Nanoplastics are then magnified through marine trophic networks, intoxicating several levels along the way and from the cellular level [See examples of articles showing negative effects of microplastics on zooplankton, fishes, whales, and humans]. Therefore, plastics have the most devastating impact in areas with the greatest diversity of species and pristine sites, as fragments persist for good and take more than a lifetime to really disappear.

So, how can we remove all this plastic from the Ocean, or at least, how can we reduce the amount that ends up there?

The challenge of managing solid waste and investing in recycling by industries and countries represents an open tap in any movement concerning reducing marine pollution. Every day new solutions appear to reduce plastics within the production line, which are launched on the market, with varying prices and technologies. Around the world, take-away packaging has increased a lot with the pandemic panorama, and more than ever it is necessary to innovate packaging technology.

Terrawpackages and New Gen BioPBS, as well Earth Cup are using new technologies with Hybrid Cane Molded Pulp Cups and Bamboo Fibers or Plants Fibers that can be biodegraded in natural conditions in 60 days. Likewise, smart cities are a new-age trend and the movement towards efficient human settlements is a reality from urbanized areas to small fishing villages. Substituting plastic for natural fibers and polymers has many adepts like Chitosan, a natural polymer and one of many other materials to be investigated as a raw material for bioplastics. Although it is still in the development phase. Short-term solutions focus on improving waste management techniques to prevent plastics from entering the ocean in developing countries, however, long-term solutions aim at major changes in the system, such as a transition to the circular economy.

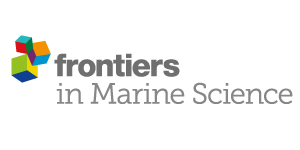

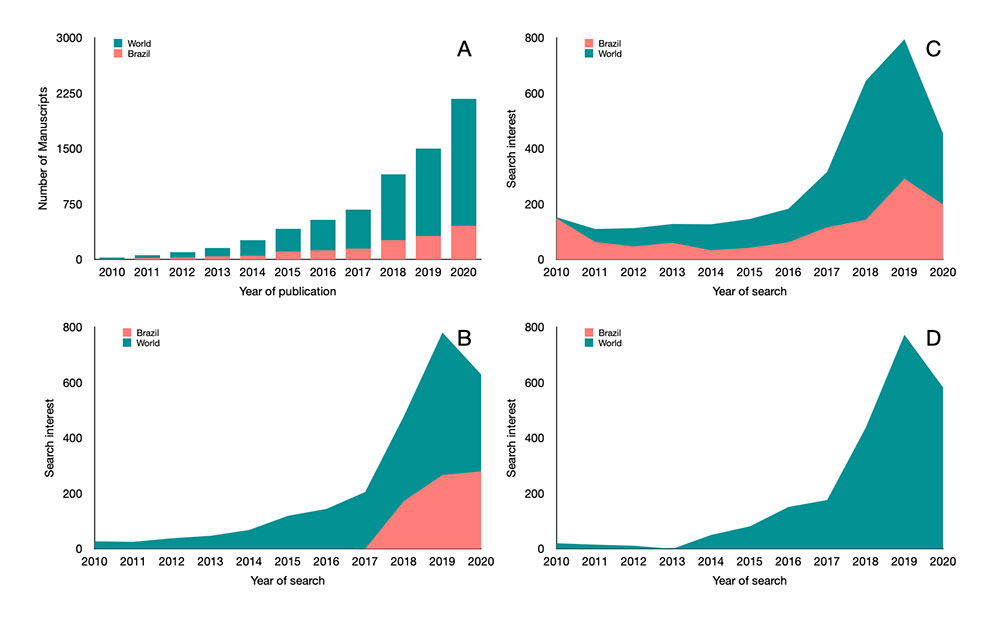

Essential to any solution is the introduction of behavioral changes in consumers. For this reason, education and awareness are essential for the implementation of any solution and require that all stakeholders are involved and work together. As scientists and advocates work harder, society becomes more aware of the harms that plastics are causing to marine and human life and seeks ways to help. Scientific publications about marine litter and microplastics in the ocean have increased with an average 55 percent yearly rate in the last decade, with data from all around the world. Accordingly but not as fast, there has been a gradual change in public interest about these topics, with 18 to 23 percent average more searches each year [Data from Google Scholar and GoogleTrends in supplementary material].

Communities Taking Action

Communities Taking Action

The best solution is always the one built by many hands. In order to design a more sustainable future for humanity with an ocean clean of plastic, people must act together. Several communities have already started this bottom-up movement and the positive effects are concrete. In Brazil, clean-up initiatives [e.g., Route Project Brazil, Green Wave, ONG Eco Local Brazil] are gathering around 20 thousand people every year, removing more than 19.6 tons of waste of plastic from beaches, rivers, and mangroves. Offshore plastic is targeted by international programs that seek to remove at least some part of our garbage [check The Ocean Cleanup movement and its fleet]. Understanding the plastic patterns in the Ocean and monitoring its impacts are being carried out by research groups and environmental agencies that aim to increase evidence to corroborate a global change [Global Partnership on Marine Litter].

Environmental monitoring programs are currently being carried out for the most diverse purposes and must be implemented as part of plans to combat waste at sea by the various environmental programs such as the World Surfing Reserve Program, Beach Monitoring, Megafauna Monitoring, and Surveillance of Fishing. This cleaning wave has become popular with increasing public support and volunteering through beach clean-ups and citizen science initiatives, which advocate for a more sustainable lifestyle.

Considering the unknown grounds and the vast amount of plastic in the Ocean, we understand that change comes with the development and implementation of effective strategies and engaged people. As detailed, marine litter is a real problem with several challenges, but solutions are available to be tested and improved.

We cannot forget the importance of advancing environmental regulations to manage marine litter and meet multiple stakeholders. In each country and context, key questions should be asked: Which regulatory system is best suited to our reality? Can we adapt to all governmental levels? A genuine movement for change, with defined goals, scientific evidence, laws, market-based instruments, voluntary agreements and information, as we have seen in several countries leading the movement to combat marine litter. The first steps are starting bottom-up and legitimate the global actions for a Clean Ocean.

Acknowledgments:

We thank: the Brazilian Long-term Ecological Research Program Coastal Habitats of Espírito Santo (PELD HCES), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel CAPES for Mazzuco's postdoc fellowship; and Deep Blue Associação Ambiental for the support on fieldwork in Itajaí and data management. A special thanks to all the volunteers who participated in the beach sampling and Eco-magazine for the opportunity to communicate our research.

Cited links and references:

https://oceanpanel.org/

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106274

https://www.oceandecade.org/about?tab=our-vision

https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2014.03.en

https://www.un.org/Depts/los/global_reporting/WOA_RPROC/Chapter_25.pdf

https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X18785730

https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10127

https://www.ourbluehands.com.br/

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/microplastics/

https://news.un.org/pt/story/2019/05/1671792

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-60630-1

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.065

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00039

https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1913

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/smart-cities/

https://routebrasil.org/

https://www.greenwave.org/

https://ecolocalbrasil.org.br/

https://theoceancleanup.com/

https://www.gpmarinelitter.org/

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15611

https://www.savethewaves.org/wsr/

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/centrotamar/projeto-de-monitoramento-de-praias

https://oceantrackingnetwork.org/

References for further reading:

UNEP, 2016. Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics – Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

Lusher, A.L., 2015. Microplastics in the marine environment: distribution, interactions and effects. In: Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M. (Eds.), Marine Anthropogenic Litter.

Springer, Berlin: pp. 245–307 https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-319-16510-3_10

Turra, A., Manzano, A.B., Dias, R.J.S., Mahiques, M.M., Barbosa, L., Balthazar-Silva, D., Moreira, F.T., 2014. Three dimensional distribution of plastic pellets in sandy beaches: shifting paradigms. Sci. Rep. 4:1–7 (4435). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04435.

Smagiloiva E., Hughes L., Rana N., Dwivedi Y. (2019) Role of Smart Cities in Creating Sustainable Cities and Communities: A Systematic Literature Review. In: Dwivedi Y., Ayaburi E., Boateng R., Effah J. (eds) ICT Unbounded, Social Impact of Bright ICT Adoption. TDIT 2019. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 558. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20671-0_21

Peixoto, J.R.V. 2005. Morphosedimentary analysis of Santinho Beach and its relationship with the structure and dynamics of the “pioneer” vegetation of the frontal dune, Island of Santa Catarina, SC, Brazil. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

Monteiro, A. M., Furtado, S.M.A. 1995. The climate of the Florianópolis - Porto Alegre section: a dynamic approach. Geosul. 19 (20): 117-133.

Lebreton, L., van der Zwet, J., Damsteeg, JW. et al. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat Commun 8, 15611 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15611

This article is part of an online series dedicated to the UN Ocean Decade. One story will be published each week that is related to initiatives, new knowledge, partnerships, or innovative solutions that are relevant to the following seven Ocean Decade outcomes. Access the special digital issue dedicated to the Ocean Decade here.