By Martina Capriotti & Raffaele Perrotta

My name is Martina Capriotti. I’m a marine biologist studying microplastics and chemical pollution. Today I’m going to tell you a story… a sad story about the effect of plastic pollution in the ocean. But I don’t want you to be sad. Few years ago, I met the fabulous oceanographer Sylvia Earle. She told me: “Martina, plastic pollution has a negative side, but also a positive side.” “Positive side???” I was asking myself. “The bad news” she continued, “is that plastic is destroying the environment. The good news is that we now know that, and we can do something for protecting our planet.”

Only a small portion of plastics waste is recycled after use. The rest contribute to growing landfills or pollution in the environment. These days, almost eighty percent of marine litter is plastic.

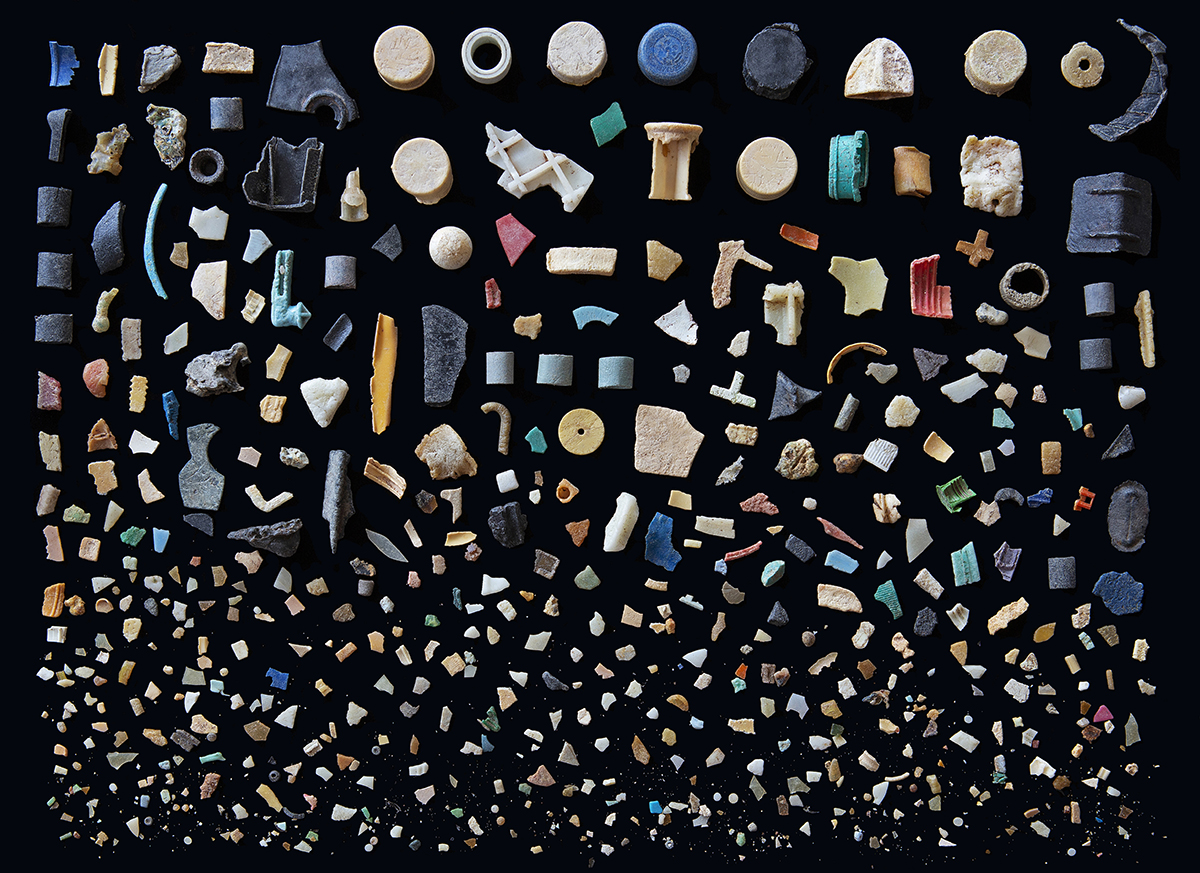

Figure 1 Pieces of plastic recovered from the stomach of ONE 90 day old Albatross chick from the Island of Midway, 2012. Photograph © Mandy Barker.

Figure 1 Pieces of plastic recovered from the stomach of ONE 90 day old Albatross chick from the Island of Midway, 2012. Photograph © Mandy Barker.

Fragmentation of a plastic bottle collected during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

Fragmentation of a plastic bottle collected during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

Plastic objects in the ocean, if not removed, are subjected to aging, mainly by UV radiation from the sun. This process leads one single plastic item to fragment in thousands of tiny particles, called microplastics.

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles smaller than 5mm. The fragmentation process leads to the production of “secondary microplastics.” The sea also contains “primary microplastics.” These are microspheres that are intentionally manufactured to be extremely small, for cosmetic uses or as abrasive pastes. There is another category of microplastics called “microfibers,” microscopic filaments released by the synthetic fabric clothes.

Microplastics spread everywhere through the currents, even in pristine areas of the ocean like the poles. As large animals eat plastic, microscopic organisms also ingest plastic in its microscopic form. Microplastics are found not only in seawater or beaches or seabed, but also inside animals. “Why should animals ingest microplastics?” I asked myself when I first heard about this phenomenon.

Many microorganisms, like bacteria or microalgae, can colonize microplastics’ surface. The life that grows on a plastic particle is called “eco-corona,” and produces many odors. Animals detect these odors and mistake it for real food. However, it is not real food. It is a trick! Once in the animal, microplastics can cause wounds in the stomach or the gut, if of sharped shape. Plastic and microplastics can also carry pathogen microorganisms and several chemicals that are toxic for living beings. Some of these toxicants are plastic additives, so are already inside the material, because added intentionally during plastic production. Other dangerous molecules contaminating sea water, can attach on the surface of plastic debris, together with the “eco-corona” described above. When plastic is ingested, these substances intoxicate the organism entering the food web.

Chemical contaminants can be hazard in several ways. Body stress, DNA damage, and hormonal disturbances are few examples. A group of these substances called “endocrine disruptors” is able to mimic hormones. They act on behalf of hormones generating confusion in the hormonal system, causing for example reproductive problems and diseases. That’s why I like to call them “molecular impostors”.

FISA trainees collecting microplastics and small plastic object on the beach during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

FISA trainees collecting microplastics and small plastic object on the beach during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

Microplastics and small fragments collected during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

Microplastics and small fragments collected during the SRAP campaign. Photo credit: Martina Capriotti

“If we do that every time we train, and if all my FISA colleagues in Italy do the same, we will see less and less plastic ending up to the sea – hurting animals or becoming microplastics,” I started to brainstorm on my way back home that day. I called FISA President Raffaele Perrotta right away and he said “Approved”. That’s how the idea of the Sea Rescuers Against Plastic (SRAP) campaign originated.

There is more. Lifeguards work every summer all over the Italian coasts. The beaches are highly populated with tourists. During the summer, an additional threat is the trash left behind by sunbathers. Lifeguards involved with the SRAP campaign are educated in the importance of reducing plastic pollution. They are the first to avoid single-use plastic. They are educated in correct methods of recycling. And they can potentially create a “green wave” that touches beachgoers, amplifying the effect all throughout the community.

All of us can do something to help safeguard the planet. I always say: “The planet will change with everybody’s small actions, not from somebody’s big action.”

References

- IUCN, 2018. https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/marine_plastics_issues_brief_final_0.pdf

- WHO, 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326499/9789241516198-eng.pdf?ua=1

- UNEP, 2020. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/water-pollution-plastics-and-microplastics-review-technical-solutions-source-sea

- https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/what-endocrine-system

- https://www.hormone.org/what-is-endocrinology/the-endocrine-system

- https://www.who.int/ceh/risks/cehchemicals/en/

- https://www.fda.gov/food/chemicals-metals-pesticides-food/chemicals

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health

- M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, & M. Klages (Eds.). “Marine anthropogenic litter.” Springer, 2015.

- https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

- Cocci P., M. Capriotti, G. Mosconi, A. Campanelli, E. Frapiccini, M. Marini, ... & F.A. Palermo. “Alterations of gene expression indicating effects on estrogen signaling and lipid homeostasis in seabream hepatocytes exposed to extracts of seawater sampled from a coastal area of the central Adriatic Sea (Italy).” Marine environmental research, 2017, 123: 25-37.

- E. R. Kabir, M. S. Rahman and I. Rahman. "A review on endocrine disruptors and their possible impacts on human health." Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. 2015, 40.1: 241-258.

- Godswill and A. C. Godspel. "Physiological Effects of Plastic Wastes on the Endocrine System (Bisphenol A, Phthalates, Bisphenol S, PBDEs, TBBPA)." International Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. 2019, 4.2: 11-29.

- Capriotti M. et al. "The Estrogenic Potentiality of Hydrophobic Organic Pollutants Contaminating Microplastics." Ocean Sciences Meeting 2020. San Diego, United States of America, 2020.

- Capriotti M. et al. Microplastics and their associated organic pollutants from the coastal waters of the central Adriatic Sea (Italy): Investigation of adipogenic effects in vitro. Chemosphere, 263, 128090. 2021.

- Pickering and J. P. Sumpter. “COMPREHENDing endocrine disrupters in aquatic environments.” Environmental science & technology. 2003, 37 17: 331A-336A .

This article is part of an online series dedicated to the UN Ocean Decade. One story will be published each week that is related to initiatives, new knowledge, partnerships, or innovative solutions that are relevant to the following seven Ocean Decade outcomes. Access the special digital issue dedicated to the Ocean Decade here.