By: Bill Streever, ECO Contributor

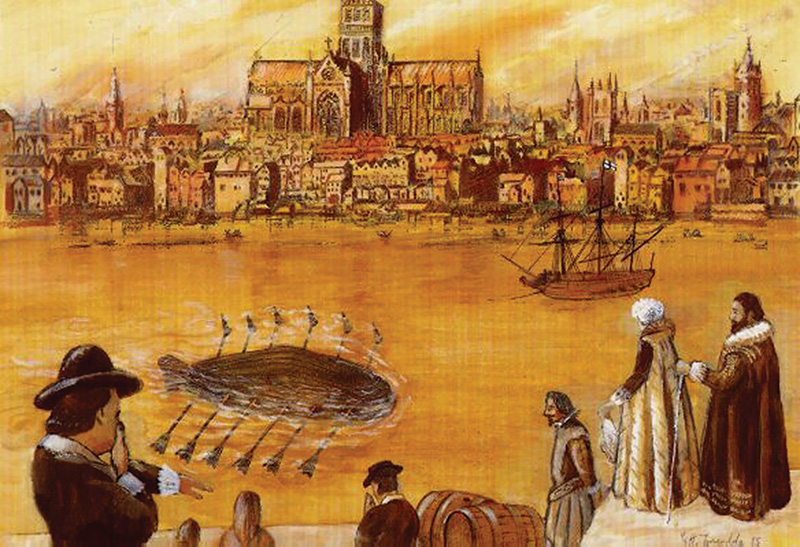

If still among the living, Dutchman Cornelis Drebbel might be justifiably proud of the vessels now under construction in a small city a mere 90 miles south of his birthplace. Why? Because in 1620, Drebbel, invented the world’s first submersible on behalf of King James I, a man who might be described as a wealthy patron. Today in Breda, a small Dutch company called U-Boat Worx creates submersibles, also on behalf of customers who might be described as wealthy patrons.

Without a doubt, there are differences between Drebbel’s creation and those of U-Boat Worx. Drebbel’s first submersible was made of wood covered with oiled leather, propelled by oars, and could not submerge more than a few feet beneath the surface. U-Boat Worx submersibles rely on wood and leather for nothing more than trim and seat covers, use battery- powered thrusters for propulsion, and some of their models are capable of diving beyond 3,000 feet.

Cornelis Drebbel built the first navigable submarine in 1620 for King James I.

Another key difference: Drebbel’s submersibles were an idea before their time. The abundance of available materials and technologies today along with a great number of potential wealthy buyers supports not only U-Boat Worx, but several competitors, including Triton Submarines and Deep Flight.

We are not talking about research submersibles here. Nor are we talking about military submarines or the tourist submersibles that are popping up (and for that matter down) at ocean resorts scattered across the globe. Here, we are talking about personal submersibles. We are talking about vehicles comparable to, say, a luxury car, but for the fact that they dive to great depths and that, well, they cost twenty times more than a typical luxury automobile.

A telephone call with Triton Submarines confirms what I suspect about personal submersible customers. “They tend to be billionaires rather than millionaires,” I am told. The submersible itself is not, after all, the only expense to be considered. There is also the support vessel, typically a superyacht. The submersible, it turns out, may cost only a fraction of the annual operating budget of the support yacht. And some customers, Triton Submarines tells me, travel with two yachts.

In a telephone call with U-Boat Worx, I wonder if customers question the cost. The response: A deep diving submersible is not exactly something that one should choose based on price. Bargain hunting and diving to thousands of feet do not mix, not even in the Netherlands, a nation known for frugality.

If I have ever regretted my utter failure to reach billionaire status, it is when I realize that I will never own a submersible capable of routinely diving beyond the reach of sunlight. Still, I am drawn to both the idea and the reality of a personal submersible as a way to explore great depths. There can be no harm in window shopping.

Inside Submersibles

Submersibles are not pressurized. Their passenger and pilot compartments carry a pressure equal to or very close to that of sea level. Submersible divers descend as deep as the strength of their vessel’s hull and hardware allows. Inside, they breathe normally. The cabin atmosphere is pulled through a chemical filter that removes exhaled carbon dioxide, and oxygen is injected into the cabin as needed. Passengers and pilots descend and return to the surface without any of the concerns that plague divers exposed to the pressures of deep water.

C-Explorer 3 passing over bow. Photo credit: Karin Brussaard 2015.

There is no requirement for decompression, and there are none of the toxicity problems that come with breathing air or other gases at great depths.

Submersibles are not diving bells. They do not hang from a surface ship, lowered down and hauled up by a winch, like the diving bell famously used by William Beebe in the 1930s to reach a depth of 3,028 feet. Instead, submersibles control their depth with ballast tanks and thrusters.

But submersibles are not submarines. Modern submarines are ships in their own right. Even World War II submarines were capable of long cruises, both submerged and on the surface. Submersibles, although not tethered like diving bells, rely on a mother ship. They are built for short trips underwater, typically a few hours at a time. On the surface, they do not function as well as an ordinary boat of a similar size.

Basic submersibles, it turns out, are surprisingly easy to build. Drebbel built not one, but three. David Bushnell of Saybrook, Connecticut, built one of wooden planks in 1775 that became known as the American Turtle. Robert Fulton, best known for work with steamboats, built one in the late 1700s that could reach depths of at least 25 feet and stay submerged for 17 minutes.

Today, hobbyists occasionally build submersibles. With materials available from local stores, high school students can and have built shallow diving submersibles. Although not a safe approach, hulls can be built from plastic sewer pipe and thrusters can be built from electric trolling motors driven by car batteries. An American man named Karl Stanley, trained in history rather than engineering, built his increasingly well-known Idabel, capable of carrying him and two paying passengers to depths beyond 2,000 feet off the coast of Roatan, Honduras.

Not to downplay the very real engineering challenges, but with modern materials and knowledge it is not so difficult to build a submersible. What is difficult is to build one that is safe, that can dive deep, and that can connect to an evolving market.

Underwater Functional Technoart

Inside U-Boat Worx, Roy de Boer, the company’s communication and marketing executive, walks me through the shop. Several submersibles are in different stages of construction. Completed models look enchanting, if not streamlined. Had Jules Verne and Jacques Cousteau shared a bottle of wine and a sketch pad, the resultant drawing may have looked like a U-Boat Worx submersible. Three words come to mind: Underwater Functional Technoart.

The company makes nine models. Each model has a unique appearance, but is immediately recognizable as a machine that belongs underwater. Here on the shop floor, on the day of my visit, a model that the company calls the C-Explorer 5 is little more than a bare hull—a transparent acrylic dome mated to an acrylic cylinder mated to a steel dome. In a month, it will be ready to dive. The now empty hull will hold stitched leather seats, a touchscreen computer system, a high-end sound system, and controls that would feel familiar to any experienced gamer. Outside, attached to the hull, the surrounding frame will hold thrusters, battery banks, spotlights, and oxygen tanks. Also, owners can choose to include various options, such as a manipulator arm.

The acrylic hull is one of the keys to U-Boat Worx luxury submersibles. Some submersibles, including most of the world’s deepest diving research submersibles, require observers to peer through small, round portholes. The acrylic hulls of luxury submersibles, like those built by U-Boat Worx and Triton Submarines, give passengers and pilots a panoramic view and what is best described as an immersive experience. On the surface, the hull is transparent but visible, like thick curved glass. Underwater, the hull, which has light transmission characteristics similar to those of seawater, becomes all but invisible. But for dry clothes and the comfortable surroundings, passengers and pilots might think that nothing separates them from the sea itself.

Like many of the parts used in U-Boat Worx submersibles, the acrylic domes and cylinders—which can be almost 10 inches thick—are built by a third-party manufacturer. They come from a British-based company that makes similar acrylic products for everything from hospital hyperbaric chambers to commercial aquariums. The touchscreens come from computer manufacturers. The thrusters come from companies that manufacture underwater robots or ROVs. The batteries, of course, come from battery manufacturers.

The pieces may not be custom made, but these submersibles are by no means spit forth by anything resembling an assembly line. At U-Boat Wrox, submersibles come together through what might be described as modular construction. At one bench, two technicians test parts. Nearby, a pressure hull is assembled. Around a corner, technicians wire batteries. Elsewhere, interior finishing touches take shape within the confines of another pressure hull, an operation that, on its surface, looks something like the construction of a ship in a bottle.

The U-Boat Worx C-Explorer 5 front side view.

The C-Explorer 5 rear side view.

The U-Boat Worx Super Yacht Sub 3.

The company began manufacturing submersibles in 2005 and has, as of the day of my visit, delivered 22 machines. The roughly 30 full-time employees build five to seven new submersibles each year. A third of the employees are engineers, and of the new submersibles built each year, at least one is likely to be a new model.

What clients want

The company, like its competitors, has to be responsive to their client’s needs. When U-Boat Worx started, there was a belief that the market was in small submersibles capable of holding an owner and a passenger. Soon it became clear that few owners wanted to pilot their own submersibles—and they wanted to bring guests along. Two seats were simply not adequate. Three-person submersibles were needed to provide space for a pilot, the owner, and at least one guest. Now, one of the U-Boat Worx models can carry nine passengers, and it is quite possible to host a small party hundreds of feet below the surface.

There is, too, the issue of launch and recovery. In most cases, owners are looking for something that can work from an existing superyacht. They also want a submersible that can be launched and recovered with relative ease. And they demand comfort. They do not want passengers aboard the submersible as it is swung over the side of the yacht, so it must float like a boat on the surface. But owners certainly do not want anything blocking the view underwater, so a large hull beneath the passengers is out of the question. One solution: the addition of inflatable tubes, similar in appearance to the tubes of an inflatable boat, that provide buoyancy and stability on the surface. Passengers board from a launch as the submersible floats on the surface. When the submersible dives, the tubes disappear, deflating under the pressure of the sea. When the submersible surfaces, the tubes re-inflate and a launch picks up the passengers before the submersible is lifted back aboard the owner’s yacht.

And through all of that—from boarding to descending to ascending to disembarking—there is the issue of safety. After all, where owners, guests, and pilots are headed, pressures approach those found inside of a halffull SCUBA tank.

Made to come up

Components are tested before assembly. The pressure hulls that protect passengers are tested before they are shipped to Holland. After assembly, the finished submersible is tested in a tank that sits behind the U-Boat Worx shop. A third pre-delivery test takes place in Holland’s Grevelingen estuary. And, finally, there is a sea trial at a location of the new owner’s choice. Before it is over, the entire submersible is subjected to a depth half again as deep as its maximum rated diving depth—a submersible intended to dive to 3,000 feet, for example, will be tested to 4,500 feet. And along the way, each submersible is certified by the independent international certification organization DNV GL.

These submersibles, despite their intended purpose, are designed to float. To dive, thrusters push down against a buoyant hull. As Roy de Boer puts it, “Our submersibles are made to come up.”

But what if, for example, a submersible becomes entangled at depth, as happened to the research submersible Johnson Sea Link in 1973 resulting in two fatalities? The parts of the modern personal submersibles most likely to become entangled, like manipulator arms, can be dropped, allowing the rest of the submersible, its pilot, and its passengers to ascend. But still, what if something went terribly wrong? Failure of the pressure hull is extremely unlikely, but what if a submersible were trapped on the seabed, despite its ability to cast off exterior parts?

U-Boat Worx sells more than submersibles. They also sell operational expertise. They provide safety plans. When a U-Boat Worx submersible dives, it is alone on the bottom, but tracked from the surface. The submersible pilot communicates with topside staff. If the worst were to occur, the pre-prepared emergency plan would be set into action. The submersible would probably release its emergency buoy. The plan might include the assistance of another nearby submersible or an ROV. In shallower water, the plan might involve technical divers, trained and equipped for short dives to hundreds of feet.

In the worst case, a submersible trapped on the bottom carries at least 96 hours of oxygen for everyone on board. The passengers might run out of champagne, but they are unlikely to suffocate before the emergency plan brings the submersible back to the surface.

Building and selling submersibles is not enough. Roy tells me that U-Boat Worx hopes to be the biggest submersible manufacturer in the world, but they want more than that. “We can’t just sell submersibles,” he says. “We have to develop an industry.”

C-Explorer 3 on the way down.

C-Explorer 3 at bridge of wreck . Photo credit: Karin Brussaard.

That means more than just delivering a submersible to a new owner and providing safety plans. U-Boat Worx also provides, for example, maintenance plans and services. Each year, one or two technicians from U-Boat Worx spends five to six days with each submersible, checking systems, keeping them running as if brand new.

But more than that, developing an industry means helping owners use their submersibles. A typical SCUBA diver with a new set of SCUBA gear needs to know where to dive—and the same is true of submersible owners. Where are the interesting deep reefs? Where are the lantern fish, the stalked crinoids, the goblin sharks? Where are the interesting wrecks in clear, deep water? As Roy de Boer puts it, “We’re assisting yacht owners by coming up with itineraries.”

And what about permits? In a world troubled by terrorism, espionage, and smuggling, many nations require permits for submersible operations. U-Boat Worx, again, has expertise on permitting available to customers.

As for owners who want their submersibles to give something back to the ocean, U-Boat Worx can even pair owners with researchers. For example, one of their submersibles, loaned by its owner to a scientific expedition, recently located Roman shipwrecks in 450 feet of water off the coast of Italy.

Competing models

As for me, my window shopping ends for now, but it would not be right to leave the impression that U-Boat Worx is the only serious submersible manufacturer. It happened that I was in Holland, so I visited U-Boat Worx. Had I been in Florida I might have visited Triton Submarines or in California Deep Flight.

In each case, I would have seen competing models and competing philosophies. At Triton Submarines, for example, I would have seen an emphasis on higher performance and deeper depths (including an as-yet-to-bebuilt design capable of reaching the hadal zone, beyond 20,000 ft), along with higher price tags. But still, I would have seen submersibles targeting what many are calling “the Luxury Submersible Market.” It is a market beyond the financial means of most consumers—but an increasingly important aspect of humanity’s exploration of the deep sea, a world that remains less known than the surface of the moon.

Triton submersibles have been operated from the Mediterranean to the Solomon Islands, from Antarctica to Tahiti.