A study has found that emissions from a chemical, CFC-11, are mysteriously on the rise despite being banned after scientists found they were depleting the ozone layer.

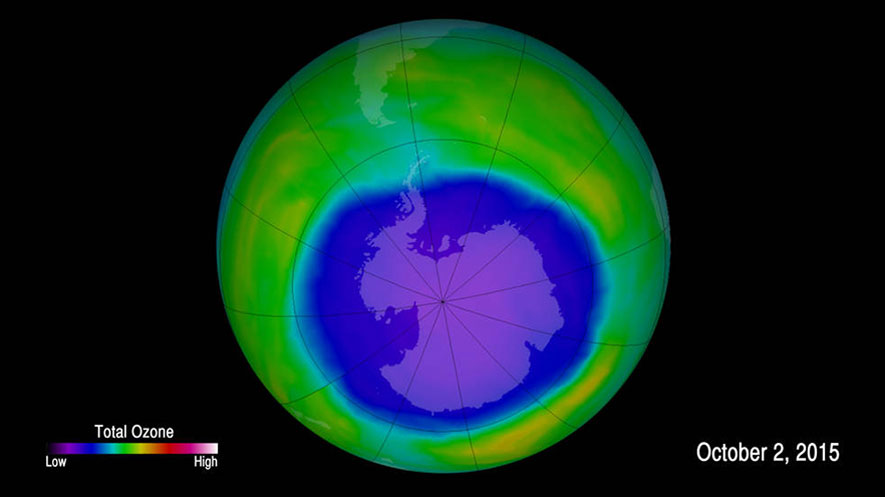

Scientists discovered in the late 1980’s that CFC (chlorofluoromethane) is the chemical family most responsible for the giant hole in the ozone layer that forms over Antarctica each September. In 1987, the international treaty called The Montreal Protocol was signed by 197 countries as a global attempt to reduce the amount of ozone-depleting substances in the atmosphere. Now a new study published in Nature on May 16, documents an unexpected increase in emissions of CFC-11 -- the second most abundant ozone-depleting gas in the atmosphere. Scientists are unsure of where these emissions are originating but suggest it is likely from new, unreported production in East Asia.

CFC was once widely used in products from aerosol sprays to fridges. Though production of CFCs was phased out by the Montreal Protocol in 2010, a large reservoir of CFC-11 exists today primarily contained in foam insulation in buildings, and appliances manufactured before the mid-1990s.

Staff at the South Pole get ready to release a balloon that will carry an ozone instrument up to 20 miles in the atmosphere, measuring ozone levels all along the way. Credit: NOAA image

Scientists from NOAA and CIRES took precise measurements of global atmospheric concentrations of CFC-11 at 12 remote sites around the globe. The data showed that CFC-11 concentrations declined at an accelerating rate prior to 2002 as expected. But the rate of decline hardly changed over the decade that followed and, more unexpectedly, the decline then slowed by 50% after 2012.

After considering several possible causes, the researchers concluded that CFC emissions must have increased after 2012. This conclusion was confirmed by other changes recorded in NOAA's measurements during the same period, such as a widening difference between CFC-11 concentrations in the northern and southern hemispheres -- evidence that the new source was somewhere north of the equator.

"We're raising a flag to the global community to say, 'This is what's going on, and it is taking us away from timely recovery from ozone depletion,'" said NOAA scientist Stephen Montzka, lead author of the paper, which has co-authors from CIRES, the UK, and the Netherlands. "Further work is needed to figure out exactly why emissions of CFC-11 are increasing and if something can be done about it soon."

Measurements from Hawaii indicate the sources of the increasing emissions are likely in eastern Asia. More work will be needed to narrow down the locations of these new emissions, Montzka said.

Because CFC-11 still accounts for one-quarter of all chlorine present in today's stratosphere, expectations for the ozone hole to heal by mid-century depend on an accelerating decline of CFC-11 in the atmosphere as its emissions diminish -- which should happen with no new CFC-11 production.

The Montreal Protocol has been effective in reducing ozone-depleting gases in the atmosphere because all countries in the world agreed to legally binding controls on the production of most human-produced gases known to destroy ozone. Under the treaty's requirements, nations have reported less than 500 tons of new CFC-11 production per year since 2010. As a result, CFC-11 concentrations have declined by 15% from peak levels measured in 1993.

That has led scientists to predict that by mid- to late-century, the abundance of ozone-depleting gases would to fall to levels last seen before the Antarctic ozone hole began to appear in the early 1980s.

However, results from the new analysis of NOAA atmospheric measurements show that from 2014 to 2016, emissions of CFC-11 increased by more than 14,000 tons per year to about 65,000 tons per year, or 25 % above average emissions during 2002 to 2012.

To put that in perspective, production of CFC-11, marketed under the trade name Freon, peaked at about 430,000 tons per year in the 1980s. Emissions of this CFC to the atmosphere reached about 386,000 tons per year at their peak later in the decade.

These findings represent the first-time emissions of one of the three most abundant, long-lived CFCs have increased for a sustained period since production controls took effect in the late 1980s.

Despite the increase, its concentration in the atmosphere continues to decrease but at a significantly slower rate than it would be without the new CFC emissions.

If the source of these emissions can be identified and mitigated soon, the damage to the ozone layer should be minor. If not, substantial delays in ozone layer recovery could be expected, Montzka said.

David Fahey, director of NOAA"s Chemical Science Division and co-chair of the United Nations Environment Programme's Ozone Secretariat 's Science Advisory Panel, said ongoing monitoring of the atmosphere will be key to ensuring that the goal of restoring the ozone layer is achieved.

"The analysis of these extremely precise and accurate atmospheric measurements is an excellent example of the vigilance needed to ensure continued compliance with provisions of the Montreal Protocol and protection of the Earth's ozone layer," Fahey said.