Millions of years ago, even before the continents had settled into place, jellyfish were already swimming the oceans with the same pulsing motions we observe today.

Now through clever experiments and insightful math, an interdisciplinary research team has revealed a startling truth about how jellyfish and lampreys, another ancient species that undulate like eels, move through the water with unmatched efficiency.

"It confounds all our assumptions," said John Dabiri, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and of mechanical engineering at Stanford Univ. "But our experiments show that jellyfish and lampreys actually suck water toward themselves to move forward instead of pushing against the water behind them, as had been previously supposed."

This new understanding of motion in fluids is published in a Nature Communications article that Dabiri co-authored with Brad Gemmell of the Univ. of South Florida, Sean Colin of Roger Williams Univ. and John Costello of Providence College.

Studying nature for clues to improve human-made technologies is part of a field called biomimetics, and the interdisciplinary collaborators originally set out to seek insights that might improve the design of submarines, ships and the like.

About three years ago, Dabiri began to suspect that scientists fundamentally misunderstood underwater propulsion, that moving forward like nature's best swimmers was far more complicated than spinning a propeller or kicking one's feet to—in a manner of speaking—push off against the water behind.

Instead, they show that as a lamprey slithers along, it creates a pocket of low-pressure water inside each bend of its body. As the water ahead of the lamprey races into this low-pressure bend, the flow of that water pulls the lamprey forward.

Jellyfish propulsion is similar. As the jelly's umbrella-shaped plume collapses, water ahead of the animal is pulled aft, propelling the jellyfish forward.

This is tricky because solids and fluids are so different.

"Interactions between solid objects are usually straightforward, like two billiard balls bouncing off each other, and therefore you can calculate the forces without much difficulty," Dabiri said. "But in a fluid every molecule is like a billiard ball and they are practically innumerable. There isn't a simple way to calculate all those interactions."

In 1755, mathematician Leonard Euler created an equation to describe fluid motion. It boiled down to the interplay of three variables: time, the rate of flow and the pressure exerted by each molecule of the fluid on its neighbors. Time and flow were easy to measure even then, but pressure is much more difficult to gauge, especially as an animal swims through the fluid.

So Dabiri's team created an experimental system that enabled them to accurately approximate this pressure variable, and it was on this achievement that the paper rests.

"Everyone appreciates that Euler's equation can effectively describe the fluid motion, but extracting the pressure from the equation in real-world experiments has been a longstanding challenge," Dabiri said.

They started with a rectangle acrylic tank about 1 ft wide, 4 ft long and 6 in deep. In the water floated millions of tiny hollow glass beads that served as proxies for water molecules. They positioned two lasers opposite each other on the thin sides of the rectangle, with a high-speed digital camera set alongside each laser.

As small jellyfish and lampreys swam through the tank, their motions perturbed the glass beads, whose positions were tracked by the lasers and recorded by the digital cameras in fractions of a second. The experiment then became an exercise in computation.

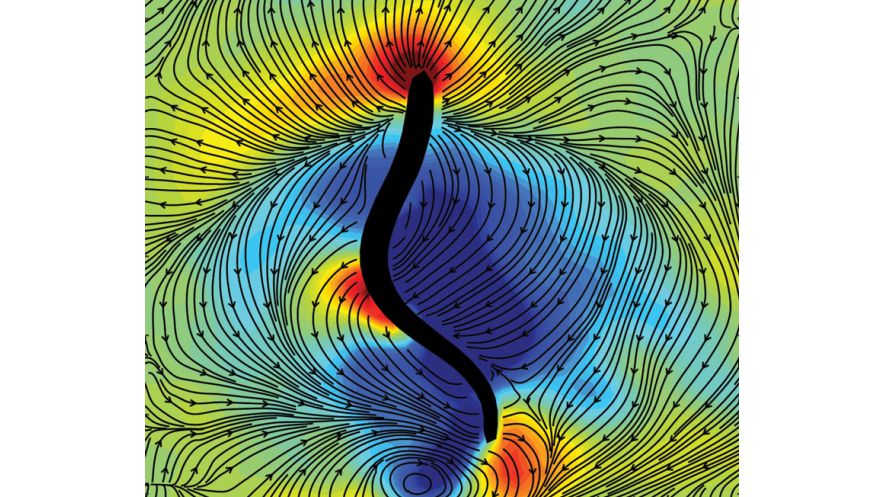

Time and flow could be precisely measured for the beads, at each moment. Making thousands upon thousands of calculations, the team used these two precise variables to solve for the third, elusive variable of pressure. They fed these results into a computer that transformed the mountain of data into a visual representation of the pressure forces at play.

From this image, it became clear that the low-pressure pockets created on the inside edge of each undulating animal movement were the dominant driver of propulsion, by pulling water toward the animal to move it forward.

As an added proof, the researchers compared two batches of lampreys of the same species. The control batch moved in natural, undulating fashion. The experimental batch were modified so that only their tail end flicked, using a less efficient kicking motion, not unlike human swimmers.

"The body undulations of the normal lampreys set them apart as much better swimmers than you and me," Dabiri said. "Human swimmers generate high pressure instead of suction. That's good enough to get you across the pool, but requires much more energy than the suction action of lampreys and jellyfish."

"For nearly 100 years, it has been assumed that mimicking natural swimming meant finding ways to generate high pressures to push water backward for thrust," Dabiri said. "Now we realize we've had it backward, and so the search is on for ways to generate low-pressure suction to achieve more efficient underwater propulsion."

Costello, a jellyfish expert, said the new findings show the mechanism selected by evolution to optimize distance-for-effort in underwater animals.

"Animals that move in fluids almost invariably use flexible, rather than rigid, propulsive structures," he said. "This work opens the door to understanding why evolution has converged upon particular bending patterns."

For more information, click here.