California sea lions have managed to maintain—and, in the case of males, increase—their average body size as their population grows and competition for food becomes fiercer.

This is in contrast to other marine mammals, whose average body size tends to decrease as their numbers increase. Researchers report in the journal Current Biology that sexual selection was a strong driving force for males to grow bigger and to strengthen muscles in their neck and jaw that help them fight for mates. Both male and female sea lions evaded food shortages by diversifying their diets and, in some cases, foraging further from the shore.

"Body size reduction is not the universal response to population increase in marine predators," says lead author Ana Valenzuela-Toro, a paleoecologist at the University of California Santa Cruz and the Smithsonian Institution. "California sea lions were very resilient over the decades that we sampled and were able to overcome increasing competition thanks to prey availability. They're like the raccoons of the sea: they can consume almost everything, and they can compensate if something is lacking."

While many marine mammal species have rebounded to some extent since the Marine Mammal Protection Act was passed in 1972, California sea lions are notable for the size and duration of their population increase: the number of breeding females, who have been most consistently counted, has more than tripled in the US since the 1970's—from around 50,000 to nearly 170,000—and their population growth is only now beginning to plateau.

To explore how California sea lion ecology has changed as their population has grown, the researchers analyzed museum specimens of adult male and female California sea lions collected in central and northern California between 1962 and 2008. To estimate changes in body size, they compared the overall size of more than 300 sea lion skulls collected over the years. They also measured other skull features, such as the size of muscle attachment points, which allowed them to assess changes in sea lion neck flexibility and biting force.

The team additionally took tiny bone samples from some of the skulls and measured their stable carbon and nitrogen isotope composition, which allowed them to make inferences about where the sea lions were foraging and what they were consuming. "Carbon provides information about habitat use—whether they're foraging along the coast or offshore—and nitrogen provides insights about the trophic level of their prey, for example if they're consuming smaller or larger fish," says Valenzuela-Toro.

Overall, the researchers found that male sea lions have increased in size, while female sea lion size has remained stable. This sex difference is probably due to the fact that size matters for male, but not female, mating success. "One male can breed with many females, and males in the breeding colony fight with each other to establish their territory," says Valenzuela-Toro. "Bigger males are more competitive during physical fights, and they can go longer without eating, so they can stay and defend their territory for longer."

Male sea lions also increased their biting force and neck flexibility over this same time period. "The neck muscles are really important because they allow them to move their head and neck more agilely, bite harder, and, eventually, win when they are fighting other males in the breeding colony," says Valenzuela-Toro.

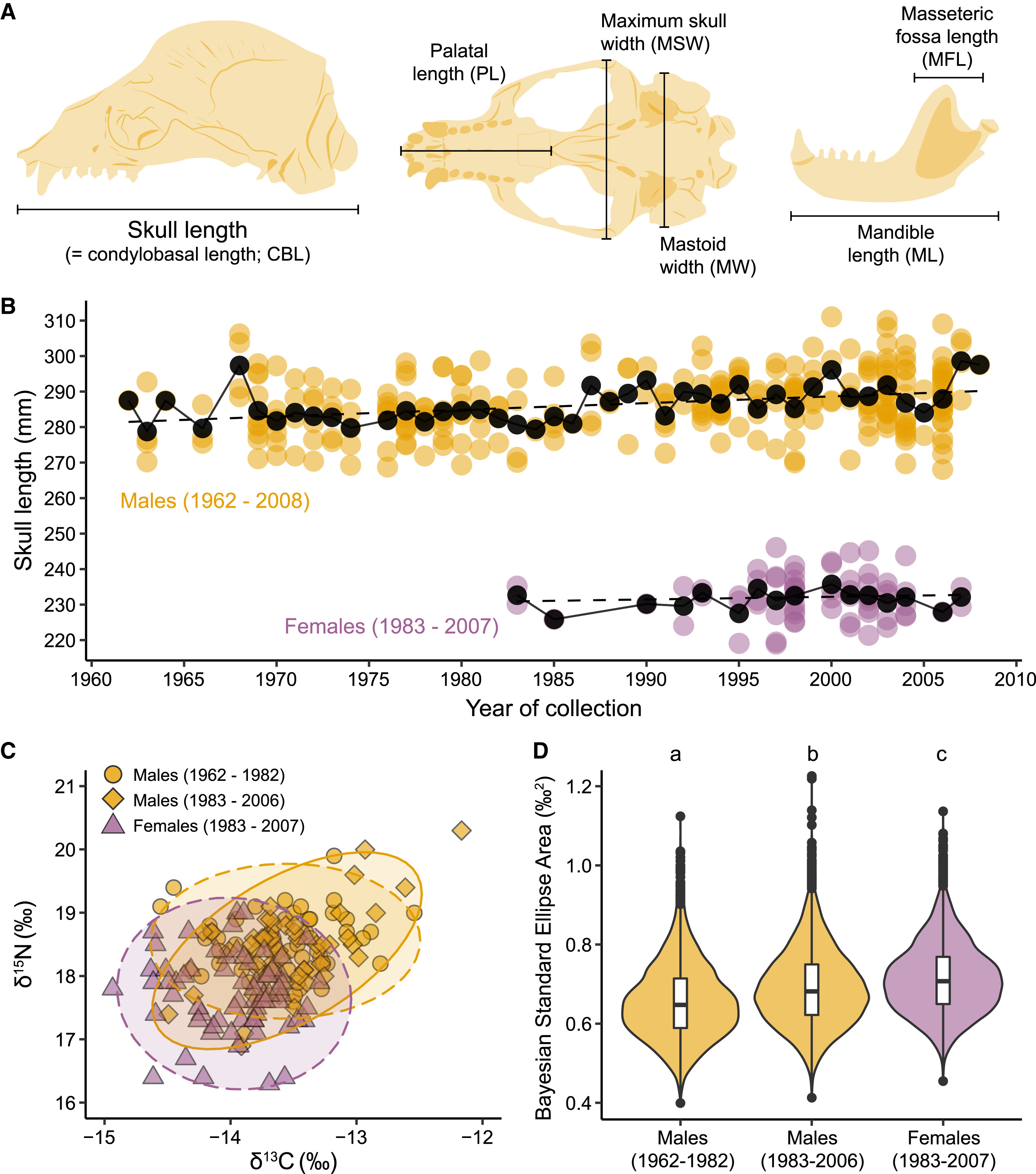

A) Skull measurements recorded in this study.

A) Skull measurements recorded in this study.

(B) Skull length of females (purple) and males (yellow) over time. Black dots represent the mean skull length per year. Dashed black lines represent the nonparametric Spearman's ρ correlation. The correlation between the skull length and the year of collection was significant for males (p < 0.0001) and non-significant for females (p = 0.92).

(C) Carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope values of females (purple triangles, 1983–2007) and males (yellow circles, 1962–1982; yellow diamonds, 1983–2006). Note that the upper temporal limit for the stable isotope analysis of males is shorter than for their morphometric analysis. Ellipses represent the size-corrected standard ellipse area (SEAC), including 95% of the data. The yellow dashed and continuous ellipses represent the SEAC of males collected between 1962 and 1982 and 1983 and 2006, respectively. Purple ellipse represents the SEAC of females.

(D) Violin plots of the isotopic niche space (Bayesian standard ellipse area) for male and female California sea lions during the same periods indicated in (C). Inset boxplots represent the median (horizontal line), inter-quartile range (rectangle), 95% range (vertical lines), and outliers (black dots). Letters on top represent significant differences between groups (p < 0.001).

(Image credit: Valenzuela-Toro et. al., 2023)

The isotopic analyses indicated that both male and female sea lions managed to meet their nutritional needs by diversifying their diet and feeding on a broader range of prey. Male sea lions also foraged further afield. "Over time, some male sea lions were foraging further north," says Valenzuela-Toro. "This is consistent with some anecdotal records that they've even been seen in Alaska, where they were not known to go in the past."

Female sea lions consistently had a more diverse diet compared to male sea lions. The authors suggest that this flexibility in food choice is what allowed females to maintain their average body size without foraging further away.

"They remain in a narrow zone around their breeding colony, but they still show a lot of flexibility in what they eat," says Valenzuela-Toro. "We believe that skull morphology in the rostrum—which is related to the size and shape of the mouth—probably has something to do with this flexible foraging behavior. We found that the size and shape of the mouth of females is related to the size of the prey that they consume."

However, this flexibility in diet can only take the sea lions so far, and the authors warn that the sea lions' future may not be so rosy.

"All these dynamics occurred in an environment that was rich in prey: full of anchovies and sardines, two species that are super important for their diet," says Valenzuela-Toro. "But over the last few years, the populations of these two fish have collapsed, so California sea lions are diversifying their diet to compensate, and apparently they are not doing so well."

"As climate change progresses, prey availability of sardines and anchovies will decrease even more, and eventually we will have more permanent El Niño-like warming conditions, reducing the size and causing a poleward shift of these and other pelagic fishes," she says. "It will be a really hostile environment for California sea lions, and eventually we expect that their population size will stop growing and actually decline."

Journal Reference:

- Ana M. Valenzuela-Toro, Daniel P. Costa, Rita Mehta, Nicholas D. Pyenson, Paul L. Koch. Unexpected decadal density-dependent shifts in California sea lion size, morphology, and foraging niche. Current Biology, 2023; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.026