The sun shines brightly over the Gulf of Mexico, causing the ocean surface to shimmer exposing a trail of rainbow hues that shows the oil spill heading closer to the coast. While the interaction between light and oil can seem harmless, a new study reveals that sunlight can chemically transform oil floating on the surface, limiting the effectiveness of dispersants used to clean up spills.

A research team funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) found that within hours, sunlight can change oil into different compounds that dispersants cannot easily break up. The findings, published April 25 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters, suggest that responders must consider time as a crucial factor when deciding how and where to use dispersants.

"It's been thought that sunlight has a negligible impact on the effectiveness of dispersants," said Collin Ward, a scientist at WHOI and lead author of the study. "Our findings show that sunlight is a primary factor that controls how well dispersants perform. And because photochemical changes happen fast, they limit the window of opportunity to apply dispersants effectively."

An aircraft applies dispersants to a slick of sunlight-weathered oil in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Credit: WHOI

An aircraft applies dispersants to a slick of sunlight-weathered oil in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Credit: WHOI

Oil and water: no mixing in the sea

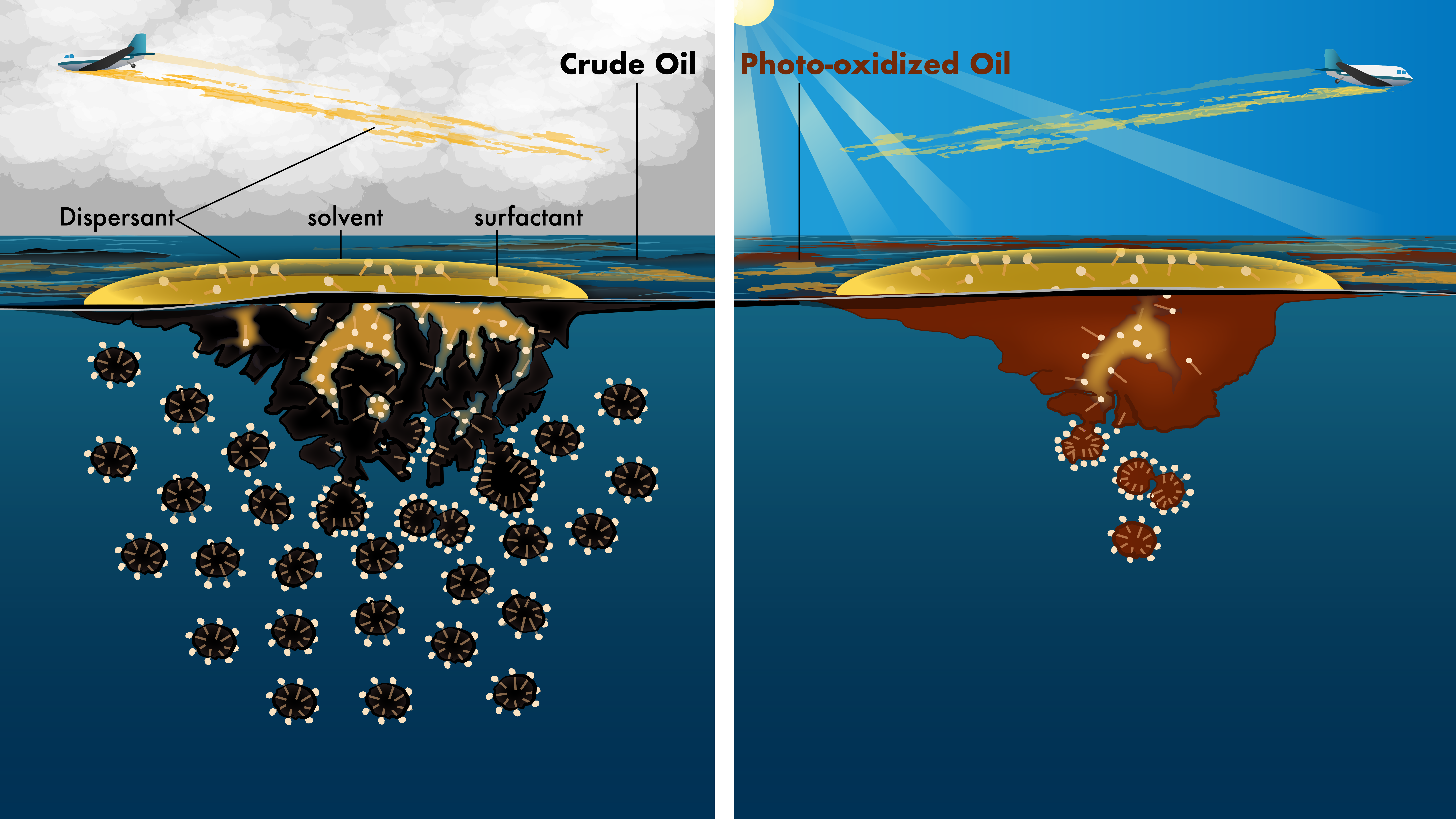

Dispersants contain detergents - not unlike those found in the kitchen - which help break oil into small droplets that are diluted in the ocean or are eaten by microbes before the oil reaches sensitive coastlines. But to do their work, the detergents (also known as surfactants) first need to mix with both the oil and water -- and oil and water, famously, don't mix.

To overcome this barrier dispersants, contain an organic solvent that helps the oil, detergents and water mix. Only when this step happens can the detergents do their work to break oil into droplets. But the new study shows that sunlight obstructs this critical step.

Sunlight changes how well oil dispersants work on spills such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. Credit: WHOI

Sunlight changes how well oil dispersants work on spills such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. Credit: WHOI

Before dispersants can be applied, light energy from the sun immediately starts breaking chemical bonds in oil compounds -- splitting off atoms or chemical chains and creating openings for oxygen to attach. This photo-oxidation process (also known as photochemical "weathering") is similar to the process that causes the colors of clothes to fade if they are left out in the sun for too long.

To date, tests to determine the effectiveness of dispersants used only ‘fresh’ oil that hadn't been altered by sunlight. In the new study, the researchers conducted extensive lab tests exposing the oil to sunlight. And they showed that sunlight rapidly transforms oil into residues that are only partially soluble in a dispersant's solvent, limiting the ability of detergents to mix with the photo-oxidized oil and break the oil into droplets.

Smaller ‘window of opportunity’ for responders

The finding suggests that responders should factor in sunlight when determining the "window of opportunity" to use dispersants effectively. And on sunny days, that window is far smaller than previously thought.

The Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig on fire at the time of the spill. Credit: Wikimedia

The continuous flow from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico provided a unique opportunity to study the effects of sunlight on oil. The WHOI scientists obtained and tested samples of Deepwater Horizon oil that were skimmed from the surface almost immediately after it appeared. They found that the longer the oil floated on the sunlit sea surface, the more the oil was photo-oxidized. The researchers also estimated that, within days, sunlight had altered half the spilled oil and reduced the effectiveness of dispersants by at least 30 percent.

The Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig on fire at the time of the spill. Credit: Wikimedia

The Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig on fire at the time of the spill. Credit: Wikimedia

The team joined forces with oil spill modeler, Deborah French McCay, from consulting firm RPS Applied Science Associates (ASA). They simulated conditions that might have occurred during the Deepwater Horizon spill - including a range of wind speeds and sunlight levels - and superimposed the 412 flight lines of planes that sprayed dispersants during the crisis.

The results showed that because responders targeted photochemically-weathered oil, the majority of dispersant applications would not have achieved minimum effectiveness levels under average wind and sunlight conditions.

Workers load chemical dispersants for application to oil floating in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: WHOI

Workers load chemical dispersants for application to oil floating in the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: WHOI

"We assembled a team that combined the expertise of academia, government, and industry researchers," added Christopher Reddy, a marine chemist at WHOI. "In future oil spill crises, the community needs the same kind of cooperation and collaboration to make the wisest decisions on how to respond most effectively."

The research was also funded by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, and the DEEP-C (Deep Sea to Coast Connectivity in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico) Consortium.