One of the planet's most active ecosystems is one most people rarely encounter, and scientists are only starting to explore. The open ocean contains tiny organisms -- phytoplankton -- that perform half the photosynthesis on Earth, helping generate oxygen for animals on land.

A study by University of Washington oceanographers, published this summer in Nature Microbiology, looks at how photosynthetic microbes and ocean bacteria use sulfur, a plentiful marine nutrient.

Sulfur is the odorous element that gives beaches their distinctive smell. The new study focused on sulfonates, in which a sulfur atom is connected to three oxygen atoms and a carbon-based molecule. In the ocean, phytoplankton use energy from the sun to create sulfonate molecules. Bacteria then consume the sulfates to gain nutrients and energy.

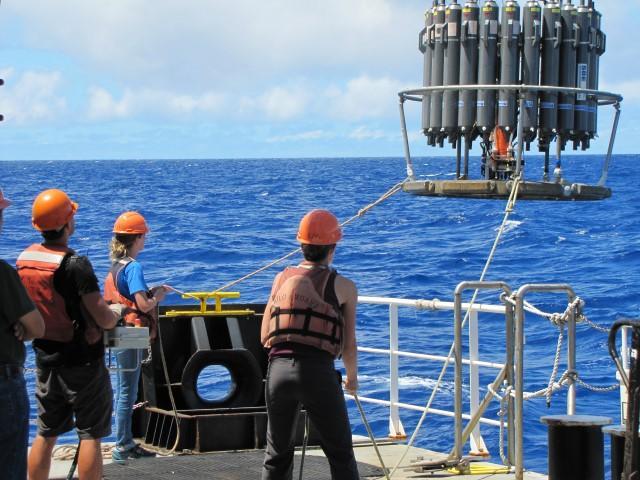

Field samples were collected during a 2015 cruise in the North Pacific. Co-authors Bryndan Durham (center) and Laura Carlson (right) recover the sampling instrument. The gray bottles open and close at specific depths to collect seawater samples. CREDIT: Dror Shitrit/Simons Collaboration on Ocean Processes and Ecology

Field samples were collected during a 2015 cruise in the North Pacific. Co-authors Bryndan Durham (center) and Laura Carlson (right) recover the sampling instrument. The gray bottles open and close at specific depths to collect seawater samples. CREDIT: Dror Shitrit/Simons Collaboration on Ocean Processes and Ecology

Bryndan Durham, then a postdoctoral researcher in oceanography and now an assistant professor at the University of Florida, drew on the recent genetic studies of soils to learn which microbial pathways are used to process sulfonates in the ocean. The study first focused on 36 marine microbes that the team cultured in the lab, using a UW-developed method to test which organisms produce sulfonates on their own in a lab environment.

The study discovered "some striking similarities between sulfonate pathways in terrestrial and ocean systems," Durham wrote in a "Behind the Paper" post in Nature Microbiology that discusses the project. Plants produce most of the sulfonates in soils. In the oceans most sulfonates are also produced by photosynthetic organisms, but in this case by unicellular phytoplankton.

The study then considered microbes in the open ocean that cannot yet be bred in the lab. During a 2015 research cruise north of Hawaii co-led by a team of researchers including Virginia Armbrust and Anitra Ingalls, both professors of oceanography and senior authors on the new study, microbial samples were collected at different times of day and night. The researchers then froze the samples in order to analyze their genetic and chemical contents back in Seattle.

"We returned from sea with a freezer's worth of samples that generated over six terabytes of data for us to explore," Durham wrote, "a major computational hurdle."

The team eventually succeeded in extracting the relevant data and found patterns that backed up the findings from the lab samples. They also detected a day-night rhythm in sulfonate metabolism that reflects the activity of photosynthetic organisms.

"Sulfonates are produced and consumed by certain groups of microbes, so we can use them to track specific relationships in seawater communities," Durham said. "And because sulfonates contain a carbon-sulfur bond, they are part of the global carbon cycle which controls the flux of carbon dioxide into and out of the ocean. This is increasingly important to understand as the climate changes."

Story by University of Washington

Journal Reference:

Read “Sulfonate-based networks between eukaryotic phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria in the surface ocean” here: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0507-5