The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 6th Assessment Report estimates that for the remainder of this century sea levels will continue to rise, leading to increasingly frequent and severe flooding in coastal areas. The magnitude of risks associated with these projections is staggering when you consider that nearly 40% of the global population lives within 100 km of a coastline and 10% of people worldwide live in coastal areas that are less than 10 m above sea level (McGranahan et al 2007). In addition to these population-based vulnerabilities, about 5% of the world’s economy is driven by trade in ocean-based goods and services. The takeaway? What impacts the coasts, impacts us all.

Comprehensive Geo-data for coastal environments—including topobathymetric maps and ocean observations—are critical to understanding the risks associated with climate change and sea level rise. That’s why government agencies large and small are urgently developing coastal resilience strategies that include Geo-data acquisition, delivery, and maintenance. It’s these programs that will enable communities to effectively plan, monitor, and act in support of safe and resilient coasts.

Coastal Resilience Starts with a Map

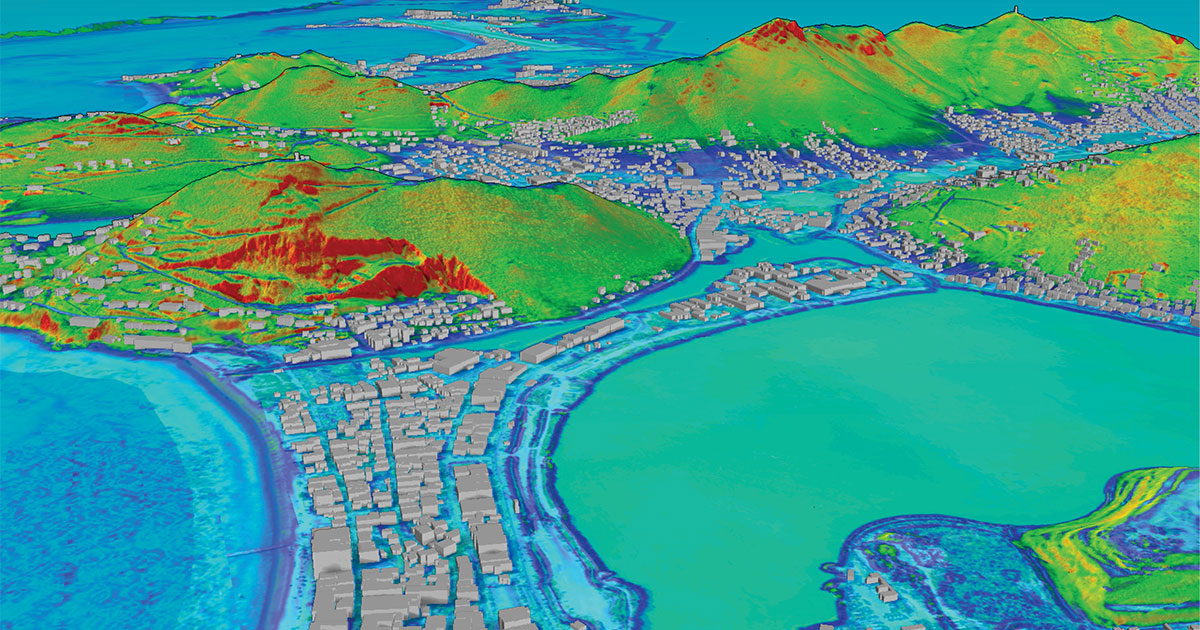

Coastal environments are complex and dynamic open systems and since a wide variety of human-centric activity takes place along shorelines, coastal Geo-data needs are diverse. Coastal mapping makes it possible to acquire, analyze, and advise on the physical characteristics of the coastal landscape, both above and below the water with Geo-data.

Historically, this work has been the remit of national hydrographic offices whose work is largely focused on maritime transportation safety and efficiency. The private sector is often called on to support these efforts. When partnership is prioritized in these contracting relationships, national hydrographic offices have shown to be a catalyst for advancing new technologies and techniques that deliver safer, more efficient, and more sustainable coastal mapping solutions.

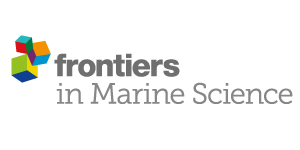

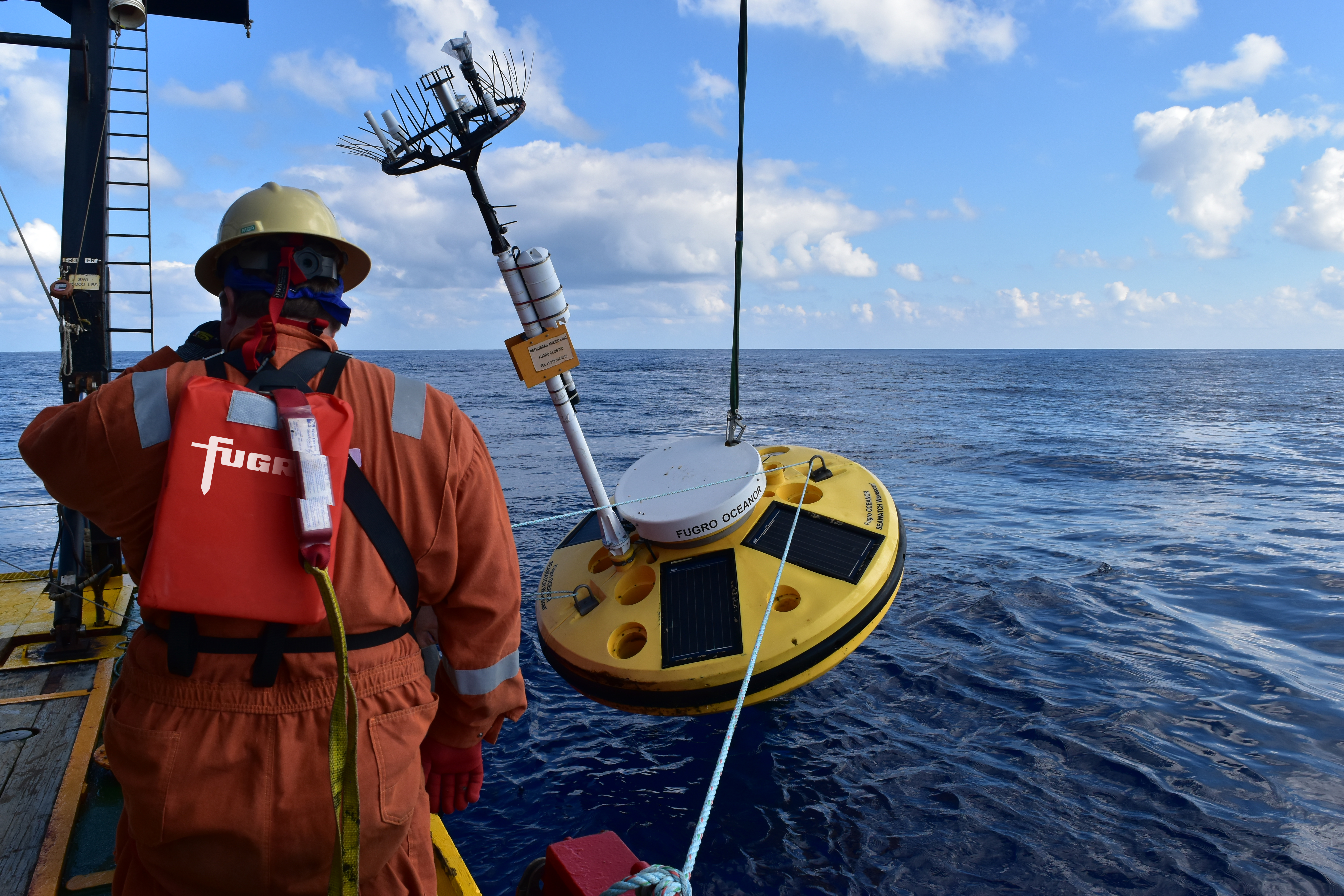

Coastal mapping can require a range of technologies, including crewed and uncrewed platforms. (Image credit: Fugro)

The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) exemplifies this concept. Responsible for delivering hydrographic and marine Geo-data to mariners and maritime organizations in the UK and abroad, UKHO requires contractors to measure and report social values including, environmental benefits. In line with these objectives, Fugro last year performed a carbon neutral survey for UKHO in the Cayman Islands. That feat was accomplished in part by using Fugro RAMMS, a next-generation airborne lidar mapping system that was initially inspired by UKHO challenging industry to improve the efficiency of lidar bathymetry surveys and quality of lidar bathymetry data. Fugro has gone on to further reduce emissions associated with lidar acquisition by developing the capability to deploy the RAMMS system from fixed and rotary wing uncrewed aerial systems (UAS). The system can even be deployed from a vessel of opportunity, enabling it to access more remote and challenging locations typical of many coastal areas.

Observational Geo-data Add Depth

Characterizing the coastal zone is more powerful when coastal mapping is combined with additional observational Geo-data, such as tidal, current, wave, biogeochemical, and environmental data for the ocean and coastal environment.

Physical ocean properties play a large role in understanding how storms and other ocean and climate-related phenomena interact with the coastline. Monitoring fluctuations in these observations can provide a time element, thus informing on which resilience efforts should be considered and whether they are likely to be effective in the longer term. On a broad scale, scientists use these data to run and validate models of climate change’s role—such as sea level rise—on a particular location, including impacts to the local environment. Consulting scientists and engineers assess these data, along with other factors, in developing and designing resilience strategies.

A Global Need with Local Urgency

Despite the overall value of national campaigns, the reality is that climate hazards manifest locally and impact local communities in unique ways. As such, national programs are often challenged to keep pace with the Geo-data demands of those who urgently need it. This is particularly true for areas with the most vulnerable communities—those lying at or close to sea level in the state of Florida for example.

To help residents address these problems, this year the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) launched a statewide coastal mapping program known as the Florida Seafloor Mapping Initiative (FSMI). The program will develop new, publicly available baseline mapping, , for all of Florida’s coastal waters within the continental shelf to support a wide range of coastal resilience activities, including resilient infrastructure, habitat mapping, environmental restoration, resource management, emergency response, and coastal hazard studies.

Recovery of a buoy deployed for acquisition of in situ meteorological and oceanographic data. (Image credit: Fugro)

Additionally, FSMI mapping data can be complemented by regional ocean observation programs managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). These include the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) and the Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS). CO-OPS and IOOS and other available observational data include information on physical ocean properties (e.g., tides and current velocities) that, when combined with mapping data, will significantly improve models for storm surges, hurricane paths, harmful algal bloom activity, pollutants, biodiversity loss, and other coastal, ocean, and climate-related phenomena by constraining variables in those models.

This local urgency for coastal Geo-data is also felt by developing nations, including those designated by the United Nations as small island developing states, or SIDS. Comprising less than 1% of the world’s population, SIDS represent 38 UN Member States and 20 non-UN Members / Associate Members of UN regional commissions that face unique social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities. Tuvalu is a notable example. The remote, low-lying island nation is comprised primarily of atolls—ring-shaped islands—and is considered among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, sitting a mere 5 m above sea level.

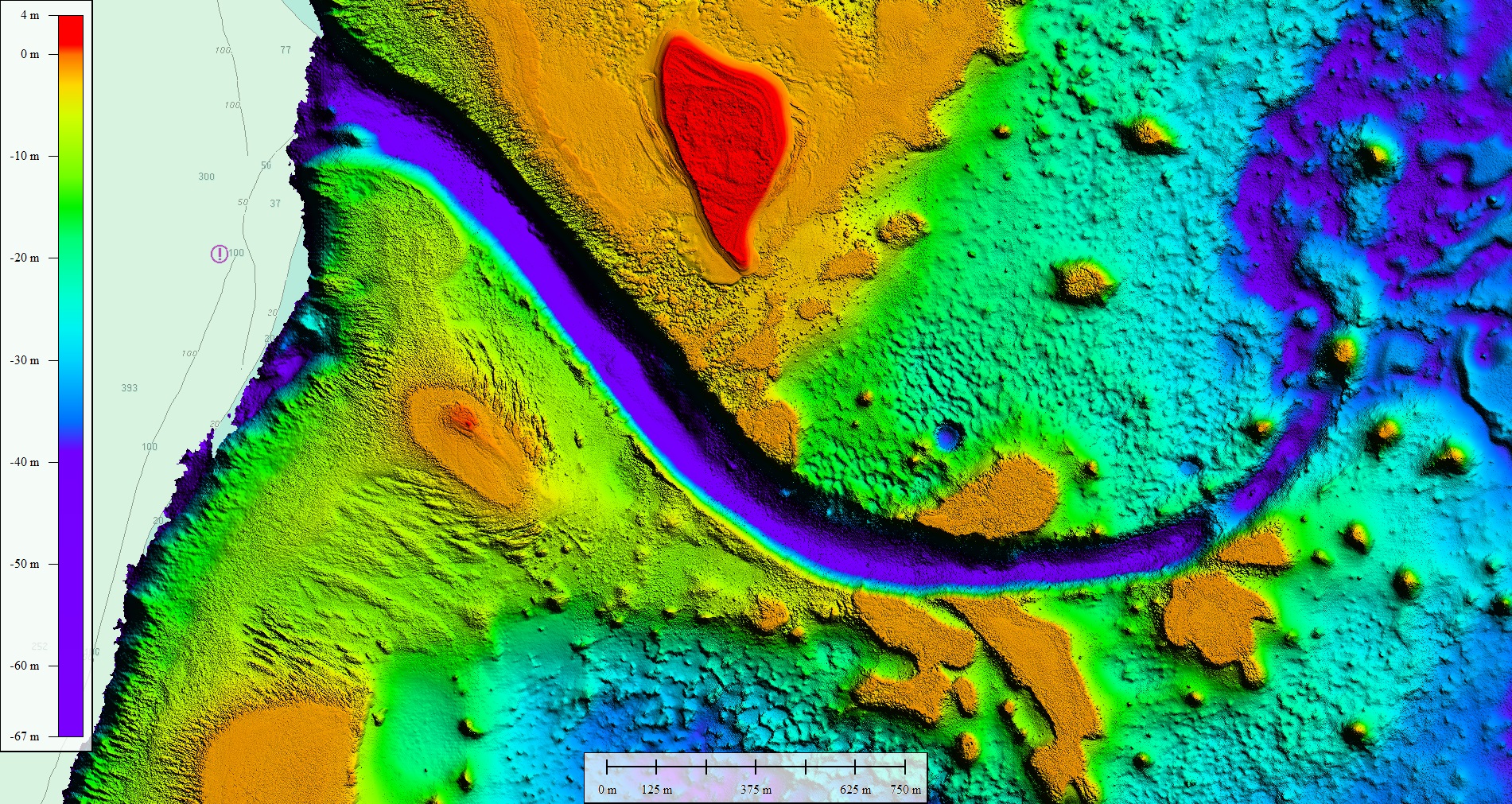

Contracted by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Fugro mapped the 26 km² island nation in 2019, providing accurate national coverage of shallow, nearshore, and lagoon bathymetry and island topography. The UNDP, with financing from the Green Climate Fund, developed the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project to conduct vulnerability assessment work that these Geo-data will feed into for analysis of vulnerability, adaptation, infrastructure development, natural resource management, and environmental monitoring needs.

Funding For Coastal Geo-data

Given the coastal Geo-data examples provided so far, perhaps the obvious question is: Who pays for these programs? The answer comes down not only to need, but also to the urgency of that need. In the US, for instance, the federal government oversees NOAA mapping programs for all 35 coastal states and U.S. territories. However, when there are widespread needs and limited budgets, which is the case in the US given >150,000 total km of coastline, delivery of Geo-data can be a waiting game…and that waiting game can prove a gamble.

Topo-bathymetric lidar of Tuvalu islands in the Pacific Ocean. (Image credit: Fugro)

What about other parts of the world, where the financial resources needed to fund such lifesaving Geo-data collection is not available at the national, regional, or local levels? In these instances, multi‑lateral funding organizations can step in to provide financial and technical assistance. The Green Climate Fund noted in the Tuvalu example is one such organization. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is another. In 2019, for instance, the University of West Indies at Mona, with financing from the IDB, selected Fugro to acquire approximately 2,000 km2 of integrated shallow water and land-based elevation data for the purpose of assessing coastal vulnerability and conducting climate analysis related to sea-level rise, storm surges and flooding in the Caribbean as part of a pilot program for coastal resilience.

Stretching Budgets Through Innovative Partnerships

As noted, even though federal and other governmental agencies may fund coastal Geo‑data acquisition programs, a considerable portion of this work is conducted by private contractors. When successful, it’s a powerful union as recognized by NOAA in their current strategic plan.

From Fugro’s experience, partnerships work best when they:

- Prioritize technical excellence, while still considering cost-effectiveness;

- Place value on technological advances in operational efficiency and reduced carbon footprint, while not sacrificing data quality;

- Consider social value, not just property value;

- Provide flexibility in contracting, allowing jobs/tasks to be performed either in bundles to decrease overall mobilization costs or collected at a time of convenience, e.g., during transit or vessel downtime.

Data Awareness and Accessibility

Equally important to data acquisition and its future utility is the question of who can access the data. Even if the data are not accessible to the public at large, awareness that Geo-data already exists in a given location can reduce the likelihood of redundancy in acquisition. When data are publicly funded, they are often made available to a broad user group. Often, however, these data are funded by private investment—such as for offshore energy—and held close at hand. Since data may be managed more locally, by those who procured it, how do we improve awareness and accessibility to this valuable information?

This is where global user groups and collaborative research efforts can be highly effective in raising awareness of data availability or gaps and accessibility. In 2017, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly announced The Ocean Decade, which aims to revolutionize ocean science in part by bringing together diverse stakeholders to generate scientific knowledge and develop the partnerships needed to support a well-functioning, productive, resilient, and sustainable ocean.

To improve awareness of and accessibility to privately-owned marine Geo-data, the Corporate Data Group was established jointly by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (IOC UNESCO), which is responsible for implementing the Ocean Decade, and Fugro.

Summary

Determining a strategy to build coastal resilience requires accessible, comprehensive Geo-data including up-to-date, high resolution coastal bathymetry and topography maps as well as ocean observations of tides, currents, waves, chemical, environmental and other physical parameters. Topobathymetric mapping, ocean observations and other Geo-data will permit baseline understanding and longer-term monitoring of our coastlines to occur so that we can create local, regional, and global strategies to adapt to these changes. Over time, these Geo-data also allow us to measure the effectiveness of implemented plans so that we may adjust our mitigation strategies based on effectiveness and changing conditions.

This feature appeared in Environment, Coastal & Offshore (ECO) Magazine's 2022 Winter edition, to read more access the magazine here.