Albatrosses have long captured the human imagination—their soaring flight and habit of shadowing ships made them an omen of both hope and peril to sailors traversing endless ocean.

It was only with the advent of tracking devices and other technologies that we have started to be able to unravel the lives of these flesh and blood creatures, but these technologies have also highlighted how close we are to losing them. 15 of the 22 albatross species are threatened with extinction, with many of the deaths being due to longline fishing vessels.

The good news is that there are simple, cost-effective ways to stop albatrosses being harmed by fishing vessels (including albatross ‘scarecrows’!). It’s just a matter of making changes across a wide scale. So in 2005, the RSPB and BirdLife International came together to form the Albatross Task Force, committed to working with fisheries all across South American and southern Africa to help save the albatross. There have already been tremendous signs of success, with both Namibia and South Africa almost eliminating accidental albatross deaths.

Here we’ll dive into the world of albatrosses and learn just how the Albatross Task Force is working with the fishing industry, communities, and governments to bring these winged giants of the ocean back from the brink of extinction.

The Albatross in Human Culture

When Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick, saw his first albatross it was an almost religious experience. He wrote that “it arched forth its vast archangel wings, as if to embrace some holy ark”, and that “as Abraham before the angels, I bowed myself.” And he is far from the first person to be inspired to godliness by these birds—the poet Samuel Coleridge envisioned the albatross as a messenger from God in his poem Rime of the Ancient Mariner, while on opposite ends of the ocean both Maori and Hawaiians have seen them as symbols of power, beauty, and wisdom.

It’s easy to see why people are so in awe of this bird: albatrosses have the largest wingspan in the world, spanning around three meters; they travel thousands of miles across the open ocean with barely a blink; and they mate for life (ostensibly, at least).

Bosun on a fishing vessel renovating a worn out bird scaring line. (Image credit: Titus Shaanika)

That’s not to say that humans’ interactions with albatrosses have been purely spiritual - albatrosses also inspire a certain sense of pragmatism. Maori used albatrosses’ down to make capes, their bones for tools, and their oil as a remedy for coughs and colds. Similarly, many European sailors would catch and eat albatrosses, as well as turning their feet into tobacco pouches and their wing-bones into pipe stems. There are also many reports of sailors shooting them for sport, desperate for activity after months of monotony on the vast ocean.

It’s only in the last half-century or so, however, that accidental deaths have become one of the defining features of the human-albatross relationship.

The Threat Between the Waves

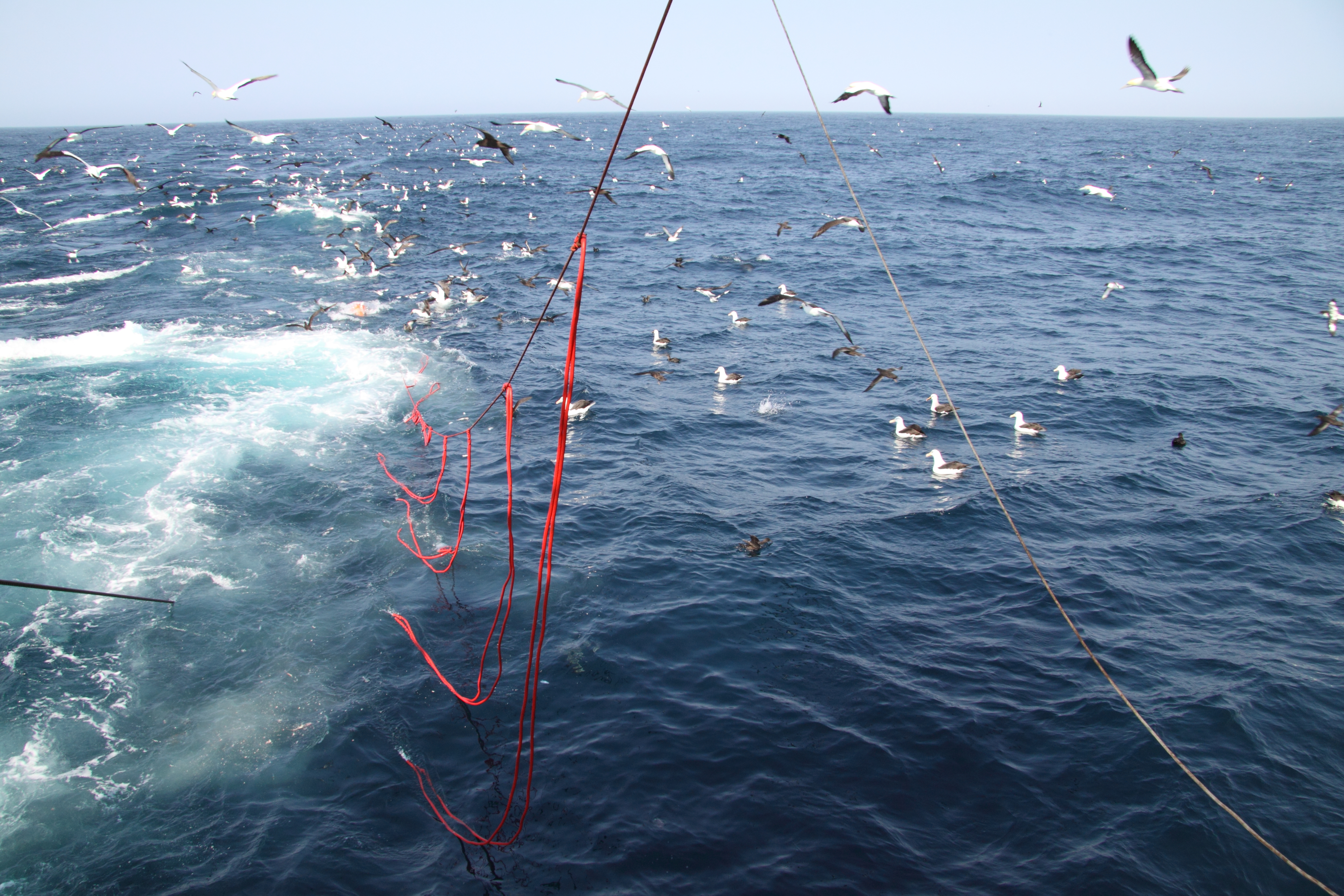

In the 1990s, fisheries’ use of longlines ballooned. This is where fishing vessels trail a long line behind the boat, sometimes up to 60 miles long (about the distance from London to Oxford) with tens of thousands of squid-baited hooks at various intervals. This has the unexpected side-effect of also catching albatrosses—they are drawn to the squid, get caught on the hooks, and are dragged beneath the waves. The boats also often use thick steel cables to haul the nets through the water, which are fatal to albatrosses in the case of an accidental collision.

These longline fisheries are now a threat to all seabirds, but particularly to the albatross. This is partly because albatrosses only have, on average, one chick every two years. Feeding this chick is a full-time job for both parents, and it then takes about five years for the chick to reach breeding age. Some species then continue to breed into their 60s. This means that each bird lost means the potential loss of a chick left with only one parent, and the subsequent loss of all their future offspring. Losing one bird is a blow, and on a wide scale can have a devastating impact.

Member of Meme Iitumbapo womens group building bird scaring lines. (Image credit: Titus Shaanika)

And these albatross fatalities are happening on a large scale. While one fishing vessel may only catch two, three, or four albatrosses in one haul, thousands of vessels spread across the ocean can spell trouble for an entire species.

The Solution? Albatross Scarecrows

The good news is there are simple, elegant steps that fisheries can take to drastically reduce albatross deaths—hang streamers and add weights!

The Albatross Task Force found that brightly colored objects can act as a kind of ‘albatross scarecrow’ and are enough to put most albatrosses off the bait. Simply adding brightly colored streamers to the fishing lines makes a huge difference. Adding weights to the cables can also save lives, by dragging cables below the water before hungry albatrosses can collide with them.

Finding the solution was only the first step, however. It’s another matter to get enough people to use them to make a difference. This was the main goal of the Albatross Task Force when they started to work in Namibia, hosted by Namibia Nature Foundation, Namibia’s leading conservation organization. Namibia’s hake trawl and longline fisheries were among the world’s deadliest for seabirds, killing an estimated 30,000 birds each year, including threatened species such as the Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross and white-chinned petrels—so it was hugely important to get them involved.

Sam and Titus from ATF on freezer trawler. (Image credit: Albatross Task Force)

The Albatross Task Force began talking to people who were involved in all aspects of the fisheries. They entered boardrooms, boarded ships, and talked with local communities to see what could help get them invested in protecting these birds. In 2015, it all culminated in a huge win for Namibia—they made it law for all demersal longline vessels and demersal trawlers (those vessels which drag nets at the bottom of the ocean) to use bird scaring lines.

In the five short years since then the number of albatrosses killed has gone down by 98 percent. As well as saving the lives of thousands of albatrosses, this is also good news for the hake fishery industry. Bird bycatch is a key consideration for whether a fishery is given sustainable seafood certification by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), and these changes mean they were recently given certification. One of the other conditions is that they continue to make improvements, so the fishing industry is going to keep working to improve their albatross safety measures in any way they can. With albatrosses having such long life spans, any measures to protect them must be similarly long-lived.

These laws were also good news for a local women’s craft group, Meme Itumbapo. They have been building bird-scaring lines to sell to the fleet for over six years now and have recently signed an agreement to partner with one of the major fisheries supply companies in Walvis Bay to continue their work. With all these groups of people invested in making fisheries safe for albatrosses, there is every hope that Namibia will continue to be a leader in making the oceans safe for albatrosses.

A Beacon of Hope Around the World

What’s particularly encouraging is that the Namibian team is the second of five ATF teams across the world to have achieved a more than 90 percent seabird bycatch reduction. In South Africa in 2014, albatross bycatch was reduced by 95 percent in the hake trawl fishery.

These results are very timely and encouraging for the UK, which is on the cusp of producing its own National Plan of Action for reducing seabird bycatch, after recent reports highlighted that the northernly cousins of albatrosses—fulmars—are being caught in longline fisheries operating off the north coast of Scotland.

Bird-scaring lines in Namibia (Image credit: John Paterson)

In the next two years the Albatross Task Force aims to work closely with communities, fisheries and governments in Argentina and Chile as well. Albatrosses travel thousands of miles, so it is only by having fisheries all around the southern hemisphere committed to their protection that they will be truly safe from that particular risk.

If you’d like to learn more about the Albatross Task Force, or about the wonderful albatrosses themselves, please visit rspb.org.uk.

This feature appeared in Environment, Coastal & Offshore (ECO) Magazine's 2021 Spring edition, to read more access the magazine here.

-Ben-Dilley.jpg)