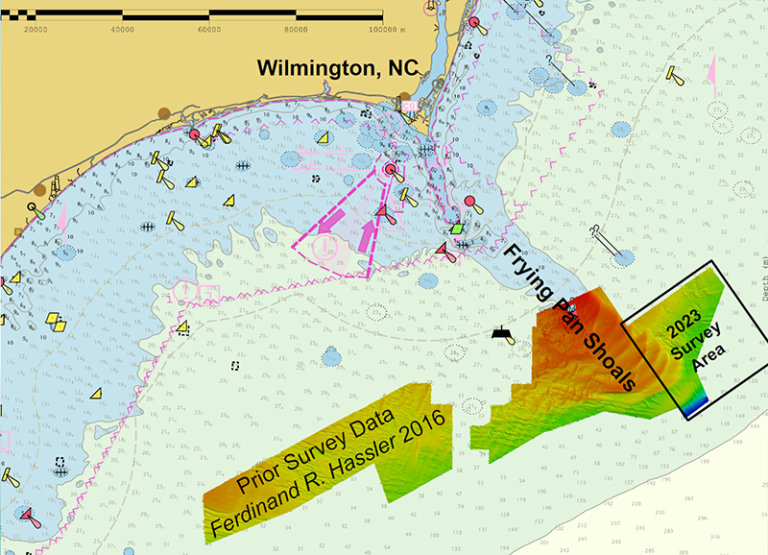

During the 2023 field season, NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler was tasked with surveying an area offshore of Wilmington, North Carolina, in the vicinity of Frying Pan Shoals—a dynamic area of dangerously shallow waters.

While scientists and crew conducted mapping surveys of the seafloor, they discovered what is believed to be well-preserved ancient remnants of a paleochannel system that could give us a glimpse as to what our North Carolina coastline looked like approximately 20,000 years ago. The location of these newly discovered paleochannels indicates that they may have once been part of North Carolina’s historic Cape Fear River and likely were above sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Wilmington is a growing port on the US Atlantic Coast now capable of handling two post-Panamax vessels simultaneously. This, plus the offshore fishing industry and the regular coastwise transit of vessels through the area, necessitated an evaluation of nautical charts around Wilmington. The data here were last collected in the 1940s and 1960s using single-beam sonar techniques. This drove NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey to request NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler survey this area to modern, high-resolution standards.

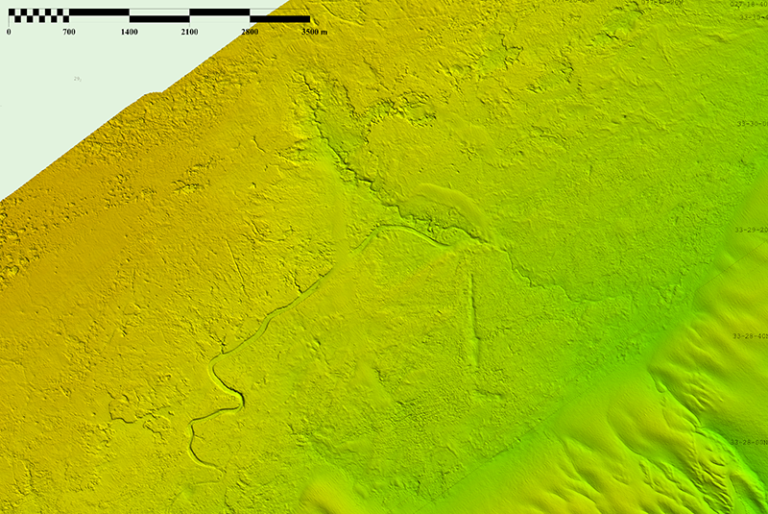

A graphic showing 2023 data gathered by NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler and adjacent high-resolution data from previous years. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A graphic showing 2023 data gathered by NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler and adjacent high-resolution data from previous years. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

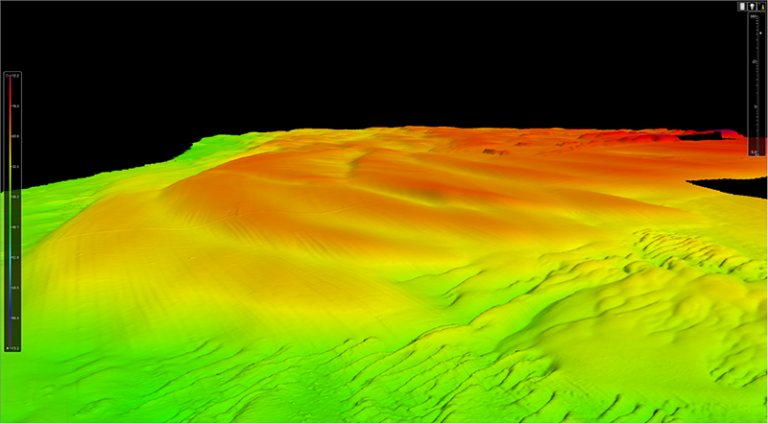

The ship employed its multibeam sonar system to map the area in high detail. As data were collected and processed, it became clear that the area was home to some impressive geologic features. Early in the survey, the crew was able to visualize a dynamic system of sand waves, likely driven by longshore currents and flow surrounding Frying Pan Shoals. Some shoals measured as large as five meters tall, with crest-to-crest wavelengths ranging from 3,000 to 4,500 meters.

A graphic showing a 3D view of Frying Pan Shoals as seen from the southeast, exaggerated 40 times. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A graphic showing a 3D view of Frying Pan Shoals as seen from the southeast, exaggerated 40 times. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

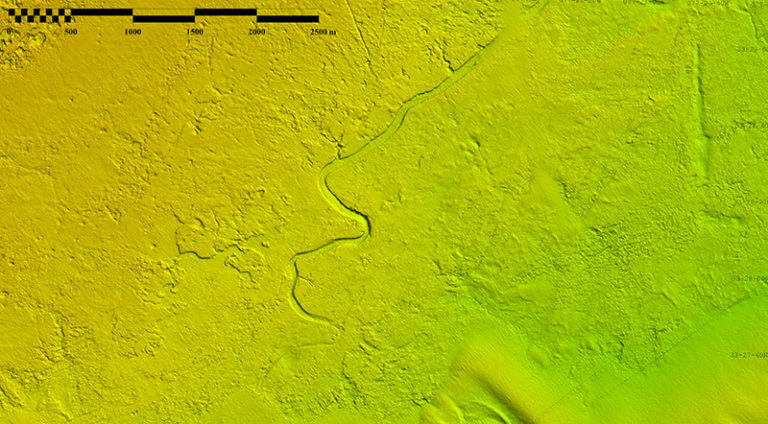

As the survey progressed further inland, more impressive features were discovered and the importance of the data being collected was being realized. The surveyors were able to observe that the seafloor was scarred by what appeared to be a system of ancient remnants of streams and rivers, formally called paleochannels. This fluvial system closely resembles the meandering rivers and streams that are seen on the coast of today’s Southeastern US coastline.

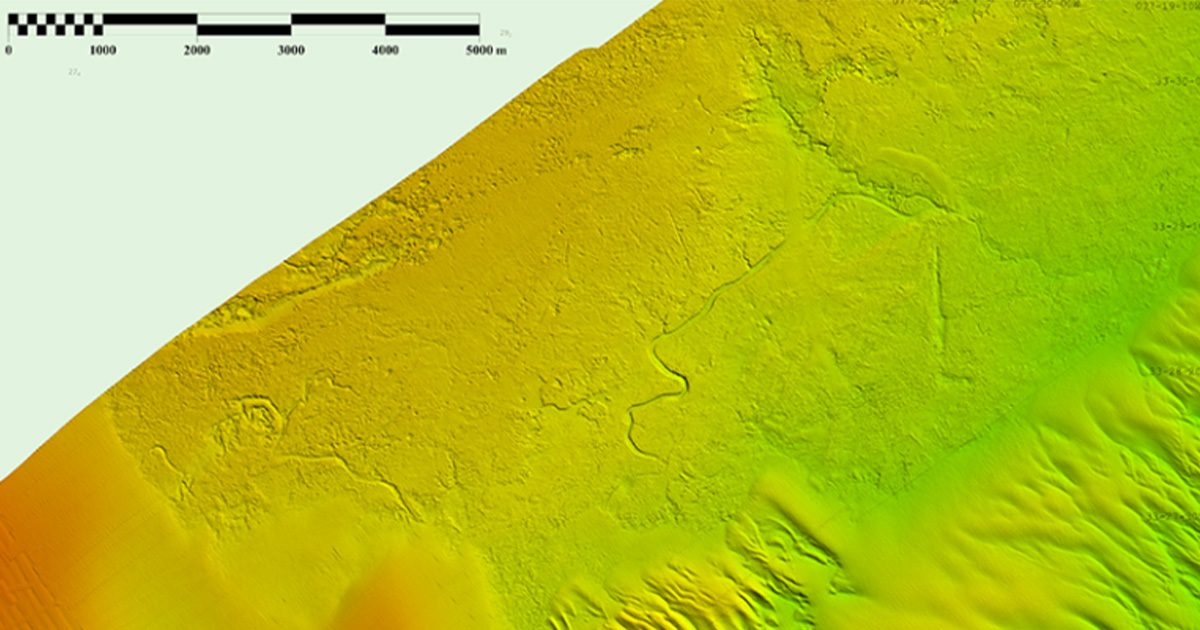

A graphic showing prominent and well-preserved paleochannel seen at 4-meter resolution. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A graphic showing prominent and well-preserved paleochannel seen at 4-meter resolution. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

These paleochannels now lie at the bottom of the ocean off of the Wilmington coast, but they were once very active fluvial systems that may have supported many species, habitats, and potentially even humans. The last time this area was above sea level was during the Last Glacial Maximum approximately 20,000 years ago, when sea level was more than 400 feet lower than it is today (Harris et al., 2013; USGS, 2024). About 15,000 years ago, the planet was warming, glaciers began to melt, and the sea level began to rise, covering all that was in its path. The location of these paleochannels indicates they might have once been a part of North Carolina’s historic Cape Fear River.

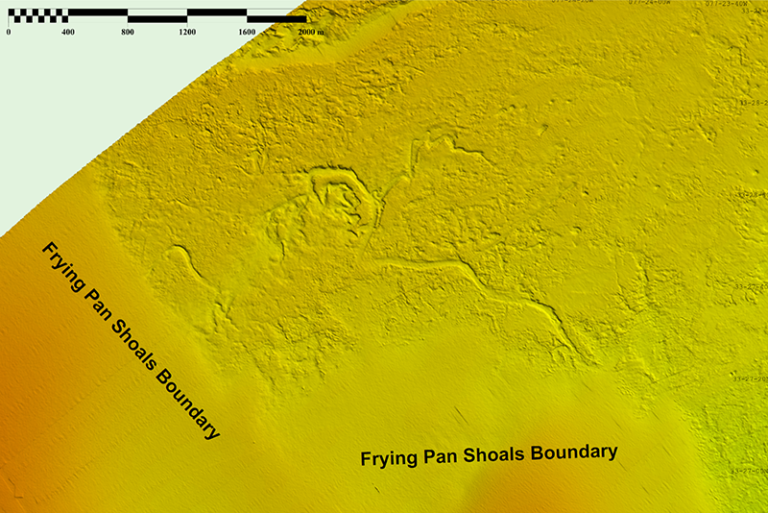

A graphic showing the southwestern corner of the most prominent paleochannel shown at 4-meter resolution. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A graphic showing the southwestern corner of the most prominent paleochannel shown at 4-meter resolution. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

Once the data were processed, Physical Scientist Alexandra (Alex) Dawson was able to identify three separate paleochannel systems that converged in several locations throughout the survey area, all appearing to be astonishingly preserved. Visual evidence such as this is rare, especially in a dynamic area such as Frying Pan Shoals. After searching numerous prior mapping surveys from years past, she observed that the only visible evidence of these well-preserved paleochannels was east of Frying Pan Shoals. How could that be?

A paleochannel nicknamed “Ear River” shown at 4-meter resolution with Frying Pan Shoals boundary directly adjacent. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A paleochannel nicknamed “Ear River” shown at 4-meter resolution with Frying Pan Shoals boundary directly adjacent. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

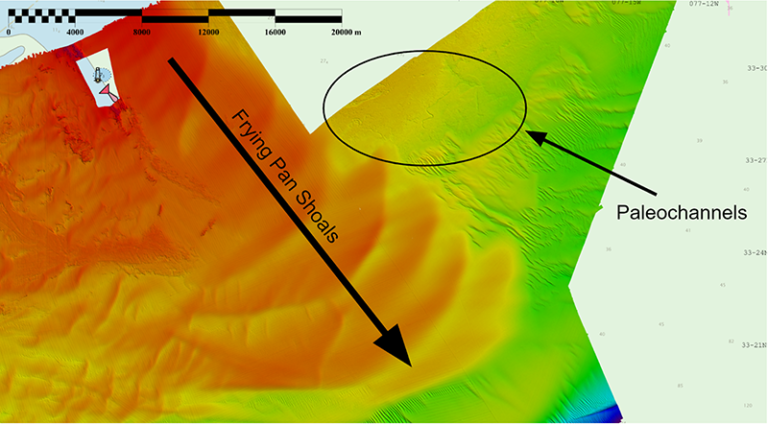

To answer this question, Alex utilized a method of estimating current direction by measuring sand wave symmetry, developed in 2018 with Dr. Leslie Sautter (Dawson, 2018). This allowed her to visualize the current and sediment movement and hypothesize how these paleochannels are so well preserved. Based on her preliminary research—which is still ongoing—Alex suggests that Frying Pan Shoals are responsible for the preservation of these historic paleochannels by acting as a barrier, shielding the paleochannels from being filled in with sediment carried by the currents.

A 4-meter resolution surface of Frying Pan Shoals, indicated by the black arrow, acting as a barrier to the paleochannels within the circle. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

A 4-meter resolution surface of Frying Pan Shoals, indicated by the black arrow, acting as a barrier to the paleochannels within the circle. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

Acquiring modern, high-resolution hydrographic data supports detailed navigational products and allows for a multitude of scientific inquiries to be addressed. Data from this survey and others like it support modern product initiatives like new nautical chart standards from the International Hydrographic Organization known as S-102. They also support national and international mapping interests in the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 project. This survey serves as a good example showing how modern technology allows for more information to be gleaned from an area that has previously been surveyed. Until now, these important geologic structures have remained elusive. These modern survey data will allow ships to navigate with confidence while also supporting accurate storm surge modeling, habitat characterization, updates to NOAA’s National Bathymetric Source, and many other uses.

NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler. (Image credit: NOAA Office of Coast Survey)

In the 2024 hydrographic field season, NOAA Ship Ferdinand R. Hassler will return to Wilmington and continue survey operations to update the nautical charts in the area. These newly discovered paleochannels continue to be researched, and the crew aboard Ferdinand R. Hassler will be on the lookout for further evidence of paleochannels this field season. Data acquired from the 2023 field season is currently under review for quality assurance. Once approved, data will be made publicly available at the National Centers for Environmental Information and incorporated into BlueTopo.