UC biologist is studying water downstream of treatment plants

Water tainted with even a small concentration of human hormones can have profound effects on fish, according to a University of Cincinnati (UC) biologist.

UC assistant professor Latonya Jackson conducted experiments with North American freshwater fish called least killifish. She found that fish exposed to estrogen in concentrations of 5 nanograms per liter in controlled lab conditions had fewer males and produced fewer offspring.

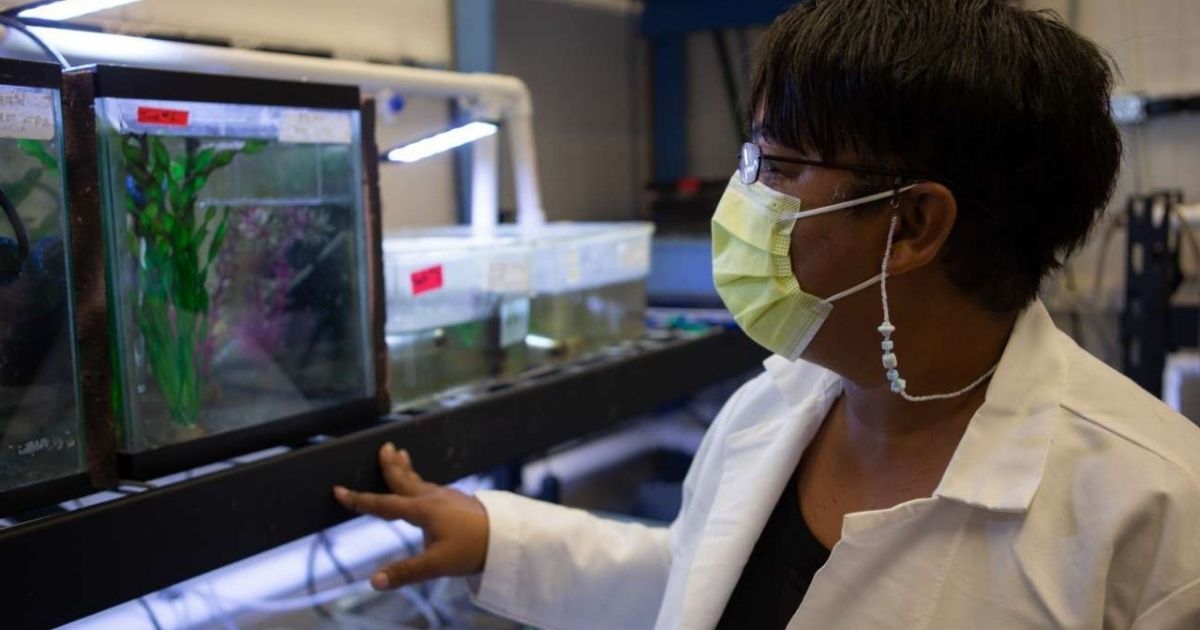

UC undergraduate Ariana Berrios works in UC assistant professor Latonya Jackson's biology lab. "In a very short period, I feel like I've learned so much," Berrios said. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC undergraduate Ariana Berrios works in UC assistant professor Latonya Jackson's biology lab. "In a very short period, I feel like I've learned so much," Berrios said. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Scientists have found estrogen at as much as 16 times that concentration in streams adjacent to sewage treatment plants.

The study suggests that even this small dose of estrogen could have significant consequences for wild fish populations living downstream from sewage treatment plants.

The study was published this week in the journal Aquatic Toxicology.

What's special about least killifish is they have a placenta and give birth to live young, Jackson said. It's uncommon among fish, who more typically lay eggs.

Jackson studied a synthetic estrogen called 17α-ethinylestradiol, an active ingredient in oral contraceptives also used in hormone replacement therapy. Estrogen been found in streams adjacent to sewage treatment plants in concentrations of as high as 60 nanograms or more per liter.

She became familiar with estrogen research while working as a medical research specialist and studying cancer. Jackson continued her work with hormones as a doctoral student and now as an assistant professor in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences.

"Anything you flush down the toilet or put in the sink will get in the water supply," she said.

This includes not only medicine people flush (never do that) but also unmetabolized chemicals that get flushed when people use the bathroom.

"Our wastewater treatment systems are good at removing a lot of things, but they weren't designed to remove pharmaceuticals," Jackson said. "So, when women on birth control or hormone therapy go to the bathroom, it gets flushed into wastewater treatment plants."

Chronic exposure of fish to estrogen led to smaller populations and a gender ratio imbalance with more females than males.

Now Jackson wants to know how the exposure to hormones such as estrogen and androgen in a female fish affects her offspring. She is collaborating with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to examine local waters in southwestern Ohio.

Jackson began using least killifish as a biological model while studying and teaching at the University of Louisiana. Least killifish are common and easily found in local waters.

What’s special about least killifish is they have a placenta and give birth to live young, Jackson said. It’s uncommon among fish, who more typically lay eggs.

The fish are tiny. Females are less than an inch long and males are half that size.

“They are considered the smallest fish and one of the smallest vertebrates in North America. They are extremely small,” she said.

That makes them convenient research subjects since they don’t need much real estate, she said.

“I can easily fit 60 to 80 in a 10-gallon aquarium,” she said.

Studying their even tinier organs is a challenge, but catching the fish is surprisingly easy, she said.

“They’re shallow-water fish. You literally stand at the water’s edge and take a dip net and scoop them up,” she said. Killifish can live more than three years in captivity. In the wild, their populations succumb to a lot of predation.

“They’re not an aggressive fish so everything eats them,” she said.

They hedge against these dangers by giving birth to live young and having a high fecundity, Jackson said. They can reproduce about every 28 days.

Jackson’s students are contributing to the research project.

“The day after coming to UC, I dove right into research involving toxicology,” undergraduate Ariana Berrios said. “I completed training to work with the fish through CITI and went on a couple field trips to ESF for experimental stream water testing.”

Now she is working on her own killifish research.

“In a very short period, I feel like I’ve learned so much,” Berrios said.

Jackson said the impacts on streams are not limited to fish. Hormones and other chemicals that are not removed during treatment can bioaccumulate in the food chain or end up in our drinking water.

"Our drinking water is not a renewable resource. When we run out of clean drinking water, it's gone," Jackson said. "It's very important that we keep this resource clean."

By Michael Miller, University of Cincinnati

Journal Reference:

Latonya Jackson, Paul Klerks. Effects of the Synthetic Estrogen 17α-ethinylestradiol on Heterandria Formosa Populations: Does matrotrophy circumvent population collapse? Aquatic Toxicology, 2020; 105659 DOI: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2020.105659