Modern mountain climbers usually carry tanks of oxygen to help them reach the summit. The combination of physical exertion and lack of oxygen at high altitudes creates a major challenge for mountaineers. Now, researchers have found that the same principle applies to marine species during climate change.

Warmer water temperatures will speed up the animals' metabolic need for oxygen, as also happens during exercise, but the warmer water will hold less of the oxygen needed to fuel their bodies, similar to what happens at high altitudes. Results of the study are published in the 5 June 2015 issue of the journal Science.

"This work is important because it links metabolic constraints to changes in marine temperatures and oxygen supply," said Irwin Forseth, program director in the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Integrative Organismal Systems, which funded the research along with NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences.

"Understanding connections such as this is essential to allow us to predict the effects of environmental changes on the distribution and diversity of marine life.”

Marine animals pushed away from equator

The scientists found that these changes will act to push marine animals away from the equator. About two thirds of the respiratory stress due to climate change is caused by warmer temperatures, while the rest is because warmer water holds less dissolved gases such as oxygen.

"If your metabolism goes up, you need more food and you need more oxygen," said lead paper author Curtis Deutsch of the University of Washington.

"Aquatic animals could become oxygen-starved in a warmer future, even if oxygen doesn't change. We know that oxygen levels in the ocean are going down now and will decrease more with climate warming."

Four Atlantic Ocean species studied

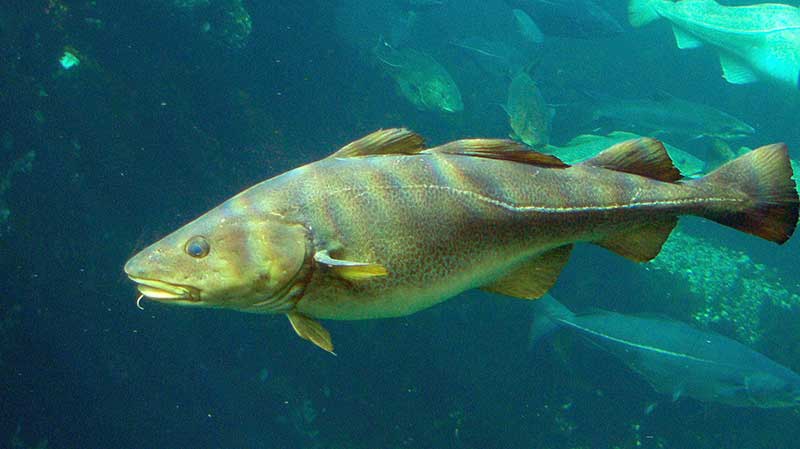

The study centered on four Atlantic Ocean species whose temperature and oxygen requirements are well known from lab tests: Atlantic cod in the open ocean; Atlantic rock crab in coastal waters; sharp snout seabream in the sub-tropical Atlantic; and common eelpout, a bottom-dwelling fish in shallow waters in high northern latitudes.

Deutsch and colleagues used climate models to see how projected temperature and oxygen levels by 2100 would affect the four species ability to meet their future energy needs. The near-surface ocean is projected to warm by several degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Seawater at that temperature would hold 5-10 percent less oxygen than it does now. Results show that future rock crab habitat, for example, would be restricted to shallower water, hugging the more oxygenated surface.

Equatorial part of animals' ranges uninhabitable

For all four species, the equatorial part of their ranges would become uninhabitable because peak oxygen demand would be greater than the supply. Viable habitats would shift away from the equator, displacing from 14% to 26% of the current ranges. The authors believe the results are relevant for all marine species that rely on aquatic oxygen as an energy source.

"The Atlantic Ocean is relatively well-oxygenated," Deutsch said. "If there's oxygen restriction in the Atlantic Ocean marine habitat, then it should be everywhere."

Climate models predict that the northern Pacific Ocean's relatively low oxygen levels will decline even more, making it the most vulnerable part of the seas to habitat loss.

"For aquatic animals that are breathing water, warming temperatures create a problem of limited oxygen supply versus higher demand," said co-author Raymond Huey, a University of Washington biologist who has studied metabolism in land animals and in human mountain climbers.

"This simple metabolic index seems to correlate with the current distributions of marine organisms," he said. "That means that it gives us the power to predict how range limits are going to shift with warming."

A day-to-day "dead zone"

Previously, marine scientists thought about oxygen more in terms of extreme events that could cause regional die-offs of marine animals, also known as dead zones.

"We found that oxygen is also a day-to-day restriction on where species will live," Deutsch said.

"The effect we're describing will be part of what's pushing species around in the future."

For more information, click here.