For island nation residents the ocean is part of our life. Growing up by the sea, we rise and fall with its sound and scent, awed by its natural beauty, and respectful of its sudden swings in mood. However, most of us are only able to truly explore and connect with the top 30 meters of our ocean. Here, sunlit thriving coral reef cities are teeming with life, but this is as much as SCUBA or freediving allows us to witness.

Go deeper and an equally rich and diverse coral reef habitats, mesophotic coral ecosystems, extend all the way down to 150 to 200 meters. Below 200 meters, what we traditionally refer to as the deep sea, lies not a vast expanse devoid of life—the mantra of scientific thinking until the late 1960s—but rather a whole new world waiting to be discovered. We now know that the deep sea is by far the largest ecosystem on Earth with the deep pelagic zone comprising over 1 billion km3 and the deep-seabed an area of 326 million km2.

By virtue of its size, the deep sea is vital for our planet’s health providing climate regulation, nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration without which life on Earth as we know it, would not be possible. It supports an astonishing biological diversity from microscopic single-celled algae to large iconic species such as sperm whales, and holds vast fishing stocks which are a major source of protein along with economic vitality and prosperity for billions worldwide.

For many marine biologists from the Global South, like myself, exploring our deep ocean is an almost impossible task. Its remoteness determines we need to utilize large oceanographic vessels. The extreme conditions of the depths dictate the need for sophisticated equipment such as remotely or autonomously operated vehicles or even submersibles. Access to these tools is prohibitively expensive and require trained personnel to operate, both of which are typically contained in higher-income countries with better access to resources and funds.

Deep-sea habitats are widespread across both international (“High Seas”) and national waters of more than 70 percent of countries. Despite this, a small number of high-income nations hold the monopoly on the research being conducted. This results in the location of data repositories, archived biological samples and the concentration of scientific expertise, that is largely concentrated in the Global North. Unsurprisingly, this has led to biases in data collected, regions explored, approaches applied, and questions addressed, leading to colonization of modern research.

‘Parachute’ or ‘colonial science’ is the practice whereby international scientists, typically from higher-income countries, conduct field studies in another country, typically of lower income, and then complete the research in their home country without any further engagement with others from that nation. The practice is exclusive and detrimental to all parties involved as it hinders the progress, uptake and application of the very research being conducted.

Recent studies into coral reef research have shown that in lower-income nations such as Indonesia and the Philippines, 40 percent of published studies included no local scientists. There is another way with fairness and equality at its heart that delivers better outcomes for the ocean, the planet and the lives and livelihoods of billions of people. There has been a growing effort seen within some organizations to diversify the voices and improve accessibility to equipment through programs like My Deepsea, My Backyard and through youth fellowships and training experiences as seen with SEAmaster in South Africa.

Nekton, a UK-based NGO, endeavors to make deep-sea research accessible and relatable to all by highlighting the mutual benefits of truly collaborative, multi-stakeholder, international projects that are built on the principles of co-development, co-production and co-dissemination. Unlike parachute science, this practice advocates for a trans-disciplinary approach to science and values the process of national leadership and engagement from inception to the application of the research project for the mutual benefit of all stakeholders involved.

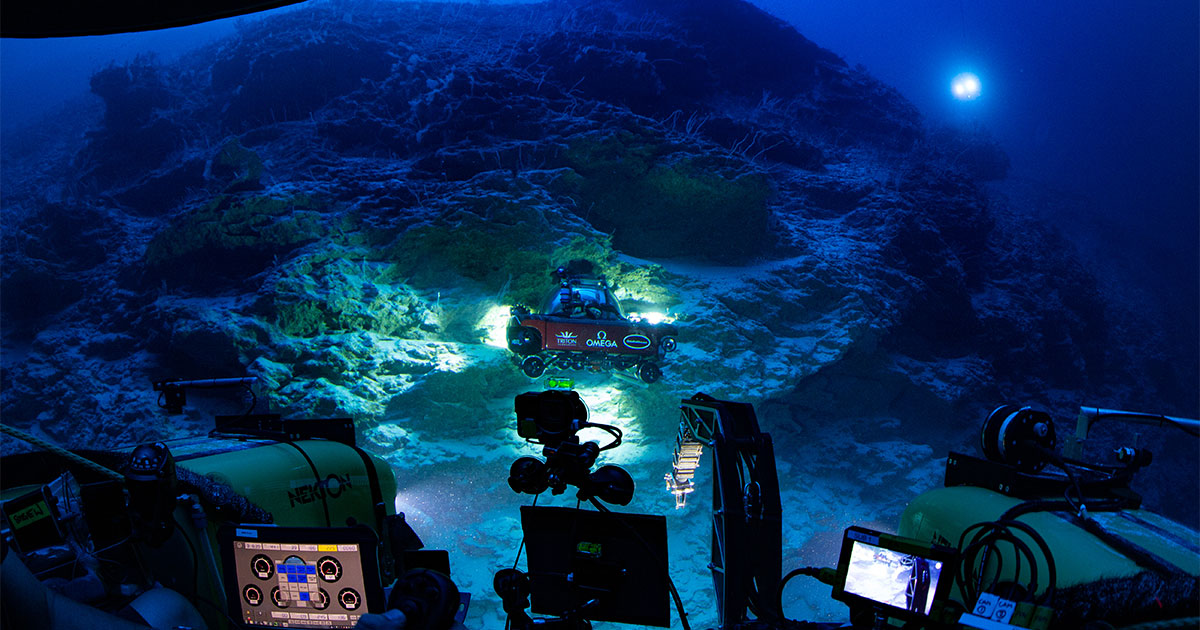

(Image credit: Nekton)

The positive interactions with Nekton and Seychelles (First Descent: Seychelles) show that truly collaborative partnerships are both possible and desirable for all parties involved. Prior to this mission, there has been very little known about what happens below scuba depths. As a large ocean state, the majority of my nation has been out of sight from human eyes, making it hard to effectively manage for future generations.

For us in Seychelles in partnership with Nekton, we had a unique platform for young marine scientists and policymakers to explore and discover the secrets of our own deep ocean using tools and equipment like ROV’s and submersibles that would otherwise be inaccessible. Our collective findings have enabled the gathering of essential data that will support management plans and sustainably manage all of our ocean.

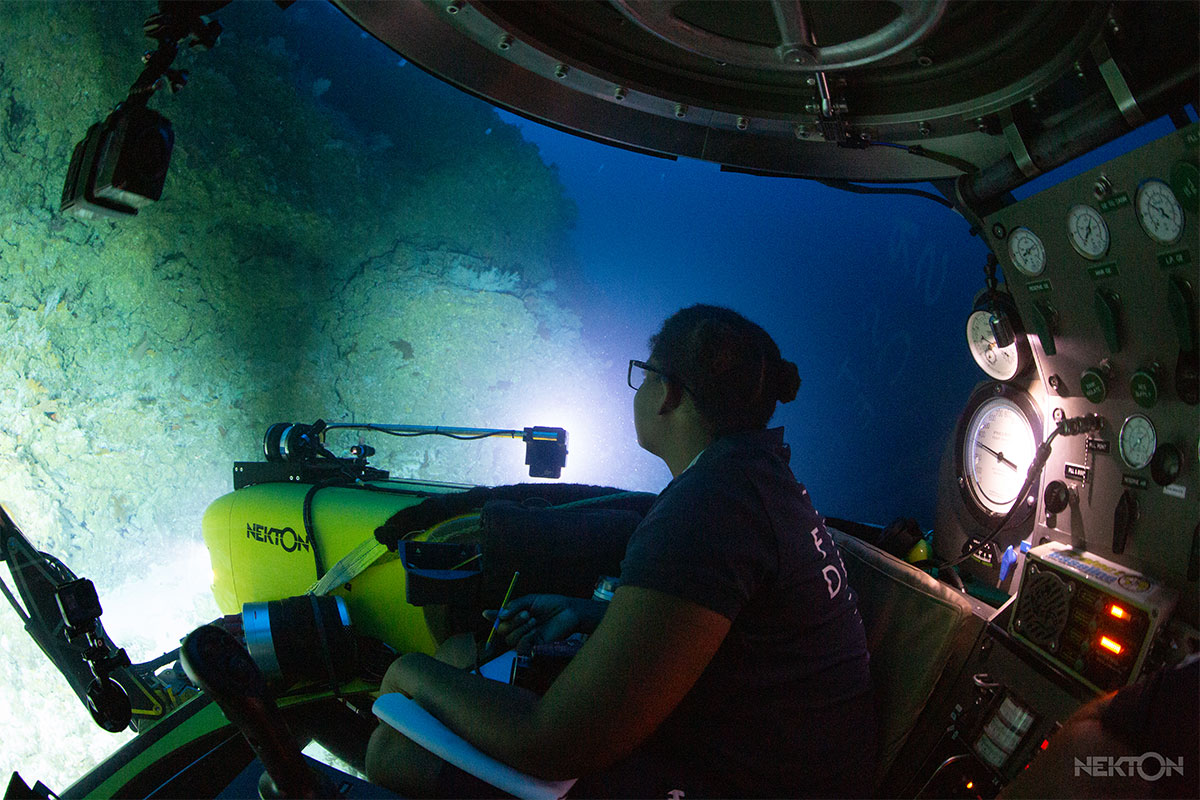

My very own experience of the deep sea has been engraved in my memory and has renewed my curiosity and passion towards a better understanding and protection of our deep ocean and our nation, 99 percent of which lies below the surface. I saw our ocean and my country in a new lens and the experience gave me a glimpse into the wonders that live at depth. The live subsea broadcasts we did from the submersibles were carried on media channels globally and within Seychelles creating national public interest and awareness.

(Image credit: Nekton)

Most importantly, my experience has highlighted the disparities and lack of equity that still occurs within science especially deep-sea research and fueled my passion to see more underrepresented groups, not just participating in deep-sea science, but leading and pioneering the field.

On a global level we can improve accessibility in deep-sea research and ensure a truly global and representative stewardship of our deep ocean through multilateral negotiations such as the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) and through international programs like the United Nations’ Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. They provide a unique opportunity to re-address these practices and for deep-sea scientists to provide a powerful unified and representative approach to investigate the ocean more equitably to benefit more of humankind.

Sheena Talma is the co-lead author of “Co-development, co-production and co-dissemination of scientific research: a case study to demonstrate mutual benefits”, published by Biology Letter, Royal Society. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0699.

Want to know more about this issue? Read Stefanoudis V Paris, Wilfredo Y Licuanan, Tiffany H Morrison, Sheena Talma, Joeli Veitayaki, Lucy C. Woodall. Turning the Tide of Parachute Science. Current Biology, 2021; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.029

This feature appeared in Environment, Coastal & Offshore (ECO) Magazine's 2021 Summer edition, to read more access the magazine here.